Education is not a public good

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Although education is not a public good, there are good reasons why the state should support education services.

First published 11 January 2018

As leader of the UK Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn has opined that “education is a public good”

and drawn the conclusion that it should all be provided by government and funded by taxation.

All three leaders of the UK Green Party since 2012 – Nathalie Bennett, Caroline Lucas and Jonathan Bartley

– have repeated the phrase “education is a public good”. They too implied that all education should be free of charge to the user and paid for out of taxation.

Similarly, Shakira Martin, who was elected President of the UK National Union of Students in 2017, remarked: “Education is a public good and should be paid for through taxation.” These influential organizations are led by people who have not learned the lessons of Econ 101.

In addition, this inaccurate rendition of the meaning of public good is common among journalists, who also have a moral responsibility to use terms accurately.

What is a public good?

The economist and Nobel Laureate Paul Samuelson established the concept of a public good in an academic paper in 1954, although some of the basic ideas involved had been formulated previously by others.

John Stuart Mill, for example, had argued in his Principles of Political Economy

that lighthouses should be built and financed by governments, because their widespread benefits could not readily be financed by passing ships, and no individual had the pecuniary incentive to construct them.

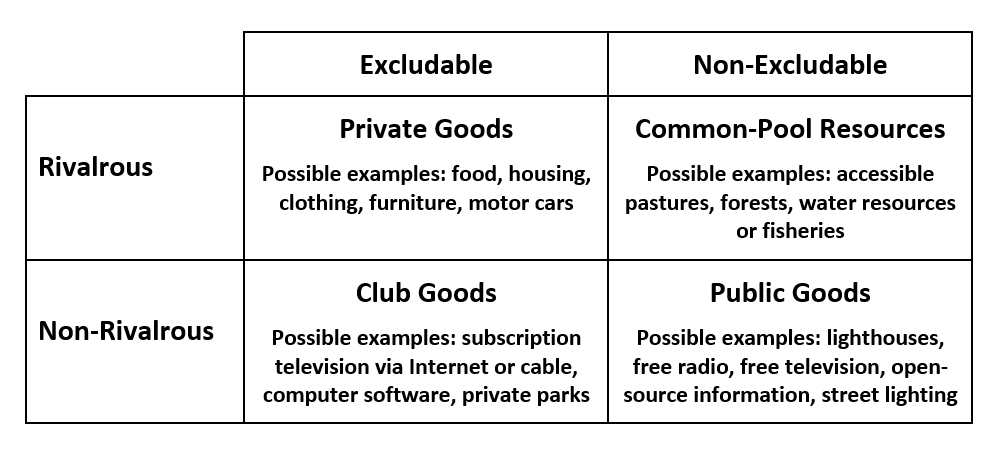

The established technical definition of a public good is a good or service that is non-rivalrous and non-excludable. Non-rivalrous means that its use or consumption by any actor does not significantly reduce the amount available for others.

Non-Rivalrous Consumption

Non-excludable means that potential users cannot practically be excluded from the use of the good or service. This definition can be confirmed by reading any reputable economics textbook.

Consider the example of street lighting. If a town council uses local tax revenues to set up and maintain lighting on its streets, then there are widespread benefits for everyone. But it is not possible to charge people individually, according to whether they benefit from the illumination.

So when elections to the town council occur, self-interested citizens will vote for candidates proposing lower taxes, assuming that they will benefit anyway from any public good provision. Why pay more taxes when the lighting is free at the point of use? Self-interested consumers will try to hitch a free-ride. The outcome is that the street lighting will be underfunded, while everyone would prefer streets that are well-lit.

Free Riders

Samuelson’s argument was popularized by John Kenneth Galbraith in his 1958 book The Affluent Society. Therein Galbraith argued that vital public goods would be under-provided in a market system: there could be the coexistence of “private opulence and public squalor”. The combined efforts of a revered mainstream economic theoretician and of an astute and inventive populariser of economic wisdom helped to pave the way for a wave of interventionist policies in the US and other developed economies.

Do public goods necessitate public provision?

After this action came the reaction. In a 1974 article Ronald Coase (another Nobel Laureate) argued that many early lighthouses in England were privately constructed and financed by tolls at the ports. In fact, an emblematic example of a public good had often been financed privately. Hence “economists should not use the lighthouse as an example of a service which could only be provided by government”.

This and other interventions led to a widespread reaction against the Samuelson-Galbraith view that public goods necessarily require public provision or public financing.

It has been pointed out that radio and TV broadcasts and open-source computer software are also public goods. Yet both are often provided by private companies. Private radio and TV broadcasters finance their broadcasts by advertising.

Computer companies sometimes make software readily available to encourage use of their computers, for which the software was designed. The software is given away to help sell the hardware, or there is a charge for support services for software users.

Whether they are desirable or not, in principle there are many possibilities for private provision of public goods. In reality there are numerous cases where the state franchises out the provision of goods or services to private contractors. Such provision could include public goods. In these cases, public financing remains, but provision is private.

The claimed advantages of private franchising would include the introduction of an element of competition between potential franchisees, and the possibilities of efficiency gains through well-focused, relatively autonomous private providers. But here again the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Many public franchising operations have failed to deliver the promised gains. Others have been more successful.

Accordingly, we end up with a pragmatic rather than a doctrinaire conclusion. Economic systems are complex, with varied, interconnected components. Theory simplifies, and does not catch all the interactive effects. Theory has continuously to be appraised in the light of empirical experience. So far it is clear than the existence of a public good does not necessarily imply that it has to be provided by government, just as there is no compelling case that its private provision will also be superior.

Misunderstanding the meaning of a public good

Careful, rational discussion of the issues surrounding vital debates over public and private provision is not simply impeded by the prevalence of opposing ideological extremes. There is also a growing and prominent disrespect for the careful use of the terms that have been established by scholars in this area.

Combinations of sloppiness and ignorance threaten the utility of key terms. They engender ambiguity, degradation and ultimate uselessness. This has already happened with swear-words such as neoliberalism. It is hoped that it does not happen with cheer-words such as public good.

A prominent misunderstanding of “public good”, is that it means “a good that can only, or should only, be provided by government”. But this conflation of public good with public provision is mistaken.

Another, even cruder, misunderstanding is that “public good” means “good for the public”. While anyone who has taken Econ 101 should spot this error, it is nevertheless widespread. Speakers sometimes give their error away when they give relative stress the “good” in the phrase, as if “good” had the meaning of virtuous or worthwhile.

Yet in the correct definition of “public good” the second word takes another commonplace meaning, denoting a possession, or an item of commerce. This second meaning is found in the pledge “with all my worldly goods I thee endow” in the Book of Common Prayer or in “the goods train went through the station”. Bad things, like tobacco, heroin, cocaine, nuclear bombs and personnel mines, are also goods in this sense.

Is education a public good?

First assume that the claims of Corbyn, Lucas and others were true: education is “good for the public” and it should be funded out of taxation, and maybe even provided by a publicly-owned enterprise.

Many additional things are “good for the public”, including clothing, food and housing. By the same logic, these “goods” should all be funded out of general taxation as well, and distributed without further charge to their users. Influential politicians thus suggest that everything that serves basic needs should be financed, and possibly distributed, by the state. The market would simply be left for luxuries. Their logic implies a state-run economy of which Stalin and Mao would be envious.

Second, even if education were a public good (by the Econ 101 definition) then this would not imply that it should be paid for out of taxation. As noted above, free radio and TV broadcasting is generally a public good, but little of it is paid out of taxation, and it would be difficult to make the case that it should be (unless we fancy a totalitarian state that does all the broadcasting and curtails all private radio and TV stations).

Third, while observing the Econ 101 definition of a public good, note that education is generally a rivalrous rather than a non-rivalrous service. Education services require resources, including buildings, infrastructure, equipment and trained teachers. Additional students generally require additional resources. (Although in some cases the marginal cost is low, such as with mass-distributed online courses.) Consequently, education provision is generally rivalrous.

Fourth, again with an eye on the Econ 101 definition, note that education services are mostly (but not entirely) excludable. Schools and universities can readily prevent other people from attending, while it is much more difficult to prevent any passing mariner from observing the light from a lighthouse.

Technically, by the standard definition, most education services are private goods, because their provision is both excludable and rivalrous. But there is no necessary reason why all private goods should be privately provided. The Econ 101 distinction between public and private goods does not readily or directly correspond with public and private provision respectively.

The parts of an education system that are actually or virtually non-rivalrous, such as massive online courses, are technically club goods. Like radio and TV broadcasting they can be provided publicly or privately.

Positive externalities in education

When students receive their qualifications, they often have advantages over others on the jobs market. Hence they reap benefits. Nevertheless, with education there are strong positive spill-over effects. Educated people help to raise the levels of public culture and discourse, and can pass on some of their skills to others. Educated people are also vital for a healthy democracy. But none of this undermines the general excludability of education services.

The spill-over effects are important, and relate to the question of public versus private provision. Another word for a spill-over is an externality: this is a cost or benefit that affects someone who did not choose to incur that cost or benefit.

Externalities can be positive or negative. Examples of negative externalities are pollution or congestion caused by motor cars. Because a driver will suffer only a fraction of the overall pollution and congestion costs of making a car journey, negative externalities impose costs on others without penalty for the car user. By standard assumptions, unless compensatory measures are taken, car use will be excessive and suboptimal.

The theory of externalities was developed by Arthur Pigou, who argued that in the presence of negative externalities some public authority should intervene to impose taxes or subsidize superior alternatives. By such measures, motor car traffic could be reduced and pollution reduced. Inversely, services such as education with positive externalities should receive subsidies or be provided free, to encourage more extensive participation in these activities.

In a famous 1960 paper, Coase dramatically changed the terms of debate with his argument that if transaction costs were zero, then all the extra costs or benefits could be subject to contractual arrangements and the externalities would disappear. For example, if the owner of every dwelling near a road had property rights in the surrounding segment of the atmosphere, then the driver of a passing and polluting car could be sued for degradation of that property. The pollution externality would be internalized.

Coase’s intention was to underline the implications of transaction costs: the existence of externalities is dependent on positive transaction costs. Coase accepted that in many cases it would be impossible to avoid the transaction burden. For example, enforcing rights in the surrounding atmosphere to curb pollution may be too expensive.

Many pro-market zealots ignored or underestimated the transaction-cost aspect of Coase’s argument. Instead, their foremost claim was that Coase had undermined the case of public intervention based on externalities.

Consider the positive externalities of education. It would be impossible or socially destructive for every educated person to charge a fee to participants in an intellectual dinner conversation, or to invoice the government for making a well-informed choice when casting his or her vote in the ballot box. The internalization of these positive externalities by such means is impossible or undesirable.

The issue of missing markets is relevant here, as I discuss in my book Conceptualizing Capitalism. There are missing markets for future employment because to introduce such complete markets would be tantamount to slavery. The prohibition of slavery means that we cannot have complete futures markets for labour. This means not simply the existence of transaction costs but the enforced absence of transactions, which would be equivalent to making the transaction costs infinite.

Consequently, because of these missing markets, education and training will be undersupplied through markets under capitalism. There is a rationale for some kind of public intervention. Of course, government intervention has its problems too. We must experiment, and compare real-world cases, not idealized models.

Mixtures of public and private provision

There are mixtures of public and private provision of education in most countries. The majority of schools in most countries are run by local government. At the other extreme, most on-the-job training is done by private companies.

The US has a mixture of private and state universities, although both types receive substantial public funds. In the UK most universities receive public money for teaching and research, and in return they are obliged to conform to a myriad of government regulations. They also receive student fees and research grants from the private sector.

Technically all UK universities are private (corporate) entities: they have a legal status equivalent to charities (which are also not-for-profit private corporations). By contrast, in several major countries in Continental Europe and elsewhere, most universities are integrated into the state machinery and all their employees are civil servants. This is not the case in the US or the UK. This international diversity of models provides the opportunity to compare different systems and determine what works best, taking account of the different contexts in which they operate.

A growing danger in world politics – including in the UK and US – is the wilful rejection of the ideas of experts, of the academic community and of science in general. Hence President Donald Trump denies the science of climate change and cries that it is a hoax. UK Cabinet Minister Michael Gove says we listen too much to experts.

I do not put Jeremy Corbyn or Caroline Lucas in the same box as Trump. Far from it. For example, they share none of his obnoxious racism and sexism. But Corbyn and Lucas are disrespecting experts and ignoring bits of science nevertheless.

We need a well-informed public conversation concerning the best arrangements for the (public or private) provision of basic needs and services, including education, health, housing and transport. Such a debate is much more difficult if leading public figures, including the leaders of major political parties, promote incorrect and misleading versions of highly relevant analytical terms.

11 January 2018

Minor edits: 12-13 January 2018

Endnotes

Note 1: As with many such definitions, there are few, if any, pure cases. So a public good refers to a good or service where consumption by one person does not significantly reduce the amount available for others, and where potential users cannot practically or generally be excluded from the use of the good or service.

Note 2: There is a widespread assumption that actors act wholly out of self-interest. But from evidence with humans in laboratory experiments and elsewhere, we know now that this is untrue. People will often agree to pay for public goods, even if they know that they have the alternative of free-riding on the contributions of others. One can conjecture, however, that numbers of people are important. We know from the work of Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom (1990) and others that cooperation is possible over the use of non-excludable resources, even when usage is rivalrous and it can degrade the resource. (Non-excludable resources that have rivalrous usage are defined as common-pool resources: they are not public goods.) But Ostrom’s examples highlight the role of face-to-face interaction and the building of trust. But it is doubtful that these mechanisms can be expanded to large-scale societies, at least without additional systems of control and enforcement.

Bibliography

Bennett, Nathalie (2017)) “#Nathalie4Sheffield – Issues: Young People”. https://www.natalie4sheffield.org/issues/young-people .

Coase, Ronald H. (1960) ‘The Problem of Social Cost’, Journal of Law and Economics, 3(1), October, pp. 1-44.

Coase, Ronald H. (1974) “The Lighthouse in Economics”, Journal of Law and Economics, 17(2), October, pp. 357-76.

Galbraith, John Kenneth (1958) The Affluent Society (London: Hamilton).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2018) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Martin, Shakira (2017) “National Union of Students Responds to PM Review of Student Funding”, NUS Connect, 1 October. https://www.nusconnect.org.uk/articles/national-union-of-students-responds-to-pm-review-of-student-funding .

Mill, John Stuart (1871) Principles of Political Economy with Some of their Applications to Social Philosophy, 7th edn. (London: Longman, Green, Reader and Dyer).

Ostrom, Elinor (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Pigou, Arthur C. (1920) The Economics of Welfare

(London: Macmillan).

Rampen, Julia (2016) “Caroline Lucas and Jonathan Bartley: ‘The Greens can win over Ukip Voters too’“, New Statesman, 21 October. https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/staggers/2016/10/caroline-lucas-and-jonathan-bartley-greens-can-win-over-ukip-voters-too .

Samuelson, Paul A. (1954) “The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 36(4), pp. 387-9.

Stretton, Hugh and Orchard, Lionel (1994) Public Goods, Public Enterprise, Public Choice: Theoretical Foundations of the Contemporary Attack on Government

(London and New York: Macmillan and St Martin’s Press).

Walker, Peter (2017) “Jeremy Corbyn: UK Firms Must Pay More Tax to Fund Better Education”, The Guardian, 6 July. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/jul/06/jeremy-corbyn-uk-firms-must-pay-more-tax-to-fund-better-education .