The Glorious Revolution of 1688

The Dutch forces of William of Orange at Torbay in Devon in November 1688

The Forgotten Invasion

© 2024 Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Some historians argue that William of Orange was "invited" to land with a large army in England in November 1688. It is true,

to give this expedition a veneer of legitimacy, Prince William asked for some leading English nobles to declare their backing. Two of the coded signatories were land magnates – one Whig and one Tory. Two more came from the army and two from the navy. A bishop completed the carefully selected list. The seven nobles wrote in their letter to William of their current "worse condition", being "less able to defend ourselves" and asked for William’s help. They also advised him on the needed size and likely popular support for his invading army. The letter did not invite William or his wife Mary to take the throne from King James II. Although they all were well-connected, none of the signatories was a legitimate representative of any political party or other organization.

Too much is made of this document by some historians. We may speculate that if Napoleon had invaded Britain in 1805 or Hitler in 1940, then in each case several prominent members of the Establishment (including some members of the Royal Family) could have been found in advance to sign a letter of invitation. The existence of such letters would have not absolved Napoleon or Hitler from the charge of invasion.

Why did William organize a risky and massively expensive military expedition to England in 1688? Crucially, the survival of the Dutch Republic was at stake. France had nearly overrun the United Provinces in 1672. Catholics had become influential in James II’s Court, and he had admitted Catholic officers into the English armed forces. Papal diplomats were trying to get France and England to join in a military alliance against the Dutch. Powerful Catholics wanted to rid Europe of Protestantism. If the Protestant United Provinces were crushed, there would be the added booty of substantial Dutch colonial territories around the world. William’s venture in 1688 was a bold move to defend Protestantism and to protect and extend Dutch influence and power.

In 1688 the French armies were tied down in campaigns in Italy and Germany. William saw an opportunity to send Dutch forces to England. His aim was not to make Britain a Dutch colony, but to bolster Protestantism and to turn Britain from a French into a Dutch ally. His purpose was regime change, not colonization.

The Dutch States General declined to formally declare its support, but it allowed William to use its army and fleet. In October 1688, the English ambassador in The Hague reported that "an absolute conquest" of England was under preparation. The invasion force comprised 463 ships, 10,692 regular infantry, 3,660 regular cavalry with horses, artillery gunners and about 5,000 volunteers. It included many English and Scottish exiles, plus mercenaries from Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and elsewhere. There were 9,142 crew members and approximately a further 10,000 men on board.

The original plan was to land on the East Coast of England. Easterly winds forced the decision to land in the Southwest. When the Dutch fleet arrived at the Dover Strait it was in lines twenty-five deep, taking several hours to pass through. It was larger than the ill-fated Spanish Armada of a century earlier.

Blessed by favourable winds, they anchored at Torbay and disembarked at the fishing port of Brixham in Devon on 5th November 1688. The infantry was all ashore by midnight. But it took two days to disembark the cavalry. Artillery, ammunition and baggage were left on board and sent by water to Exeter, because of the poor roads in Devon, and a shortage of wagons.

The Dutch army marched to the tune of

Lillibulero, composed by Henry Purcell in 1686. In his Exact Diary

of these events, John Whittie, an English Chaplain in William’s army, wrote: “This first day we marched some hours after night in the dark and rain; the lanes hereabout were very narrow and not used to wagons, carts or coaches, and therefore extreme rough and stony, which hindered us very much from making speed.”

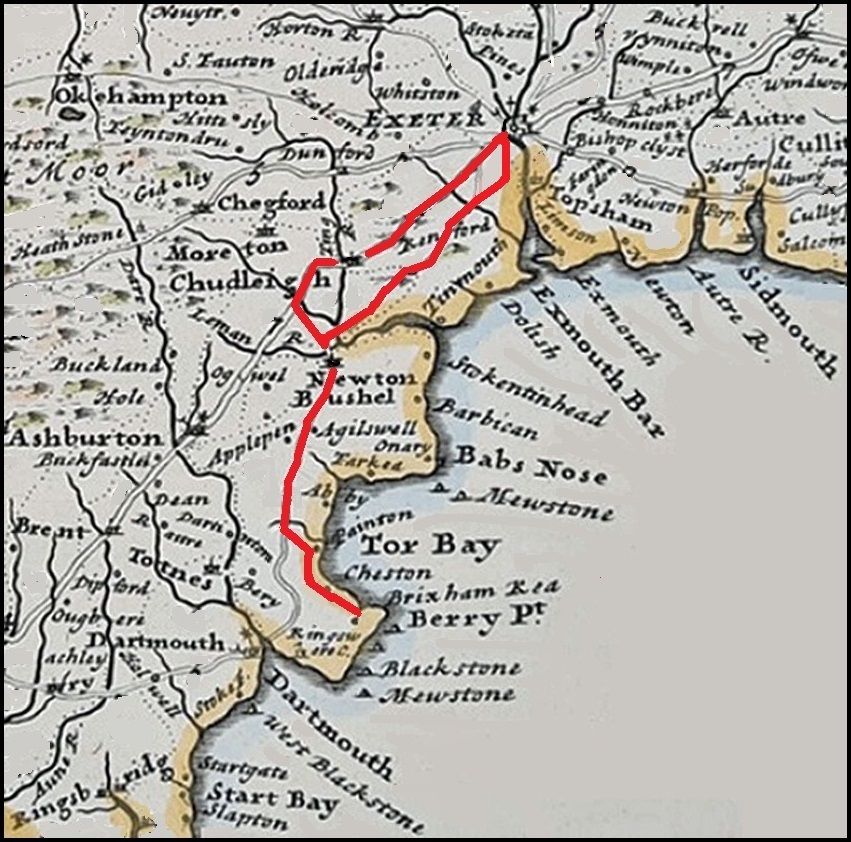

On 6th November William was at Paignton. On 7th November he was at Forde House in Newton Abbot and joined by his cavalry. On 8th November he moved up the Teign Valley to Chudleigh.

At this point his army was in two lines. William moved through Shillingford St George towards Exeter. The other part of the army went through Kenton and Exminster. An advance party with a troop of cavalry came to Exeter to prepare for the Prince’s arrival. On 9th November Prince William entered Exeter by the West Gate and processed ceremonially with his allies and troops up Stepcote Hill.

There were also "200 Blacks brought from the Plantations of the Netherlands in America" (Surinam). As this contemporary account puts it, they had "embroidered caps lined with white fur and plumes of white feathers to attend the horse." There were also “200 Finlanders or Laplanders in bear skins taken from the wild beasts they had slain, the common habit of that cold climate, with black armour and broad flaming swords.”

William spent 12 of the 42 days it took him to travel from Brixham to London, in the deanery of Exeter Cathedral. William was at Exeter with 4 battalions (about 3000 men) of infantry and 2 regiments of dragoons. The main force of cavalry was quartered round Newton Abbot. Some camped on the old Iron Age settlement at Milber Down, just southeast of Newton Abbot. Other infantry billeted in villages between Newton Abbot and Exeter, with some in the Teign Valley around Chudleigh.

William had an enthusiastic reception in Exeter, but the aftermath of Monmouth's ill-fated 1685 rebellion was blamed for the lack of immediate recruits from the local gentry and nobility. For nine days Prince William consolidated his forces. At first, he did not receive support from any local nobles. He was advised that it might be best to withdraw. But on 15th November, a group of Devon noblemen came to join William at Exeter. They included Lord Delamore, the Earls of Devonshire and Stamford, Sir Scroop How, Sir William Russel and many others. At Exeter, William received news that York, Nottingham and Bristol had been seized by rebels in his support.

Map Showing the Route of William's Army (in Red) from Torbay to Exeter

The Map was Drafted in 1724 by Herman Moll

The Glorious Revolution was not bloodless. Lord Lovelace, a radical Whig peer, led a force of cavalry to join up with the Prince at Exeter. They clashed with the Duke of Beaufort’s militia in a bloody skirmish at Cirencester. Lovelace was captured and two of his men killed.

On 19th November King James II joined his main force of 19,000 at Salisbury. On 20th November a small patrol of the English Army clashed with a detachment of the invading Dutch Army in the town of Wincanton in Somerset.

Prince William’s forces moved towards London. On 7th December at Reading, an advance guard of the Prince’s army, some 250 men strong, ran into a troop of 600 Irish dragoons, leading to over 50 fatalities. As Prince William advanced on London, the bulk of the 30,000-strong Royal Army deserted. James went into exile on 23 December.

Prince William and his army entered and occupied London.

The city and its surrounding area were placed under Dutch military occupation until the spring of 1690. No English regiment was allowed within 20 miles of the city.

New elections were held in January 1689 and Parliament was recalled for the first time since 1685. Negotiations between William and Parliament were not straightforward. Some wanted his wife Mary to rule alone, this preserving the Stuart succession. But insurrection in Ireland and a renewed French military threat against the United Provinces helped to focus minds.

Parliament made a Declaration of Right, later a Bill of Rights. Parliament agreed that by fleeing Britain, James II had lost the right to govern. William and Mary were crowned as joint monarchs in April 1689. These rights were not new. Most of them had appeared before, including in the Petition of Right of 1628. The Bill of Rights, incorporating the Declaration, received royal assent in December 1689.

Crucially, unlike preceding laws of hereditary succession, this new arrangement was an outcome of negotiation with Parliament. The acceptance of Parliament’s role in endorsing the monarch was a powerful rebuttal of the Stuart ideology of divine right to rule. Partly for this reason, the balance of power shifted from Crown to Parliament, establishing the constitutional monarchy that still exits today.

Political and Economic Outcomes of the Glorious Revolution

There were two major political outcomes of the events of 1688-89:

(1) The de facto balance of power shifted from Crown to Parliament, creating a constitutional monarchy.

(2) The Dutch enemy became an ally. England was plunged into 127 years dominated by wars with France and Spain. France and Spain were both allies before 1688.

On 10th July 1690, the French won a major naval victory at Beachy Head, temporarily gaining control of the English Channel. On the following day, King William decisively defeated former King James, at the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland. James fled to France. At that time, the French fleet was anchored in Torbay. On 26th July some of the ships traveled the short distance up the coast and attacked Teignmouth. About a thousand French troops entered the town and “in the space of three hours’ time, burnt down to the ground the dwelling houses of 240 persons of our parish and upwards, plundered and carried away all our goods, defaced our churches, burnt ten of our ships in the harbour, besides fishing boats, nets and other fishing craft”. This was the last foreign invasion of the English mainland.

James and his successors stayed in France, and it was not until 1746 (more than 57 years after 1688) when, at the Battle of Culloden, that the risk of a Stuart restoration was substantially reduced.

Britain was involved in military conflict, with at least one other major power, in 86 of the 127 years from 1689 to 1815 inclusive. The historian Niall Ferguson has ranked the twelve "biggest wars in history" by war dead as a percentage of world population. The two world wars were the largest by this measure. Six more of these "biggest" wars were in the 1688-1815 period, namely the Nine Years’ War, the War of the Spanish Succession, the War of Austrian Succession, the Seven Years War, the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. All six of these wars involved England.

War required finance. England copied Dutch financial institutions. The Bank of England was founded in 1694 to help finance the war effort. There was “Financial Revolution” and a major reform in the state administration. This institutional changes, partly spurred by war, led to the Industrial Revolution from about 1760.

These economic developments are discussed in detail in my 2023 book

The Wealth of a Nation.

Listen to my online discussion in January 2024 with Michael Liebowitz on "Unveiling the Glorious Revolution".

Some Further Reading

Badcott, Philip (2022) The March of William of Orang through Devon and his Voyage from the Netherlands

(Privately Published).

Ferguson, Niall (2001) The Cash Nexus: Money and Power in the Modern World, 1700-2000

(London and New York: Penguin).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) ‘1688 and All That: Property Rights, the Glorious Revolution and the Rise of British Capitalism’, Journal of Institutional Economics, 13(1), March, pp. 79-107.

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2023) The Wealth of a Nation: Institutional Foundations of English Capitalism

(Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press).

Jardine, Lisa (2008) Going Dutch: How England Plundered Holland’s Glory

(London: Harper).

Whittel, John (1669) An Exact Diary of the Late Expedition of His Illustrious Highness the Prince of Orange

(London: Baldwin).

This page was first published on 1st January 2024.