Impressions of War:

The Memoirs of Herbert Hodgson 1893-1974

Edited by Bernard Hodgson and Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Distribution of this volume is now handled by Martin Hodgson (hodgsonmc@aol.com).

Please contact him for prices and other information.

Published in August 2013 by Martlet Books

Cover picture: ‘The Ypres Salient at Night’ (1918) by Paul Nash.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Imperial War Museum.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Imperial War Museum.

Praise from readers of Impressions of War

‘Impressions of War is an extremely interesting and deeply moving book. I'm very interested in the First World War and aside from the fascinating detail surrounding that, the story of the lost and found Bible is both heartbreakingly sad but also strangely emblematic of the resilience of the human spirit during those times.’

William Ivory, TV script writer and screenplay writer of the films Made In Dagenham and Burton and Taylor.

‘This memoir gives us a unique insight into how “ordinary” men and women moved on from their experience of the Great War, adjusted their lives to the inter-war years, witnessed even greater bloodshed … and then re-adjusted to their “ordinary” lives once more post-1945. … The pièce de résistance of the memoir is the gentle, yet extraordinary reference to Herbert Hodgson’s contribution in turning the manuscript of T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom into the printed word. … Impressions of War is a must-read for anyone wishing to put the First World War into its proper perspective.’

Major Ian Passingham, military historian and author of Pillars of Fire: The Battle of Messines Ridge 1917, and The German Offensives of 1918: The Last Desperate Gamble.

‘Herbert Hodgson's Impressions of War provides the reader with a splendid example of the extraordinary insights that a private soldier from a working-class background was able to offer concerning life, death and conditions on the Western Front in the “war to end all wars”. What makes Herbert Hodgson’s account all the more valuable is that he clearly has a gift for writing and self-expression, enabling him to produce a memoir which is articulate, sensitive and vivid. It also contains elements which are unique and give it an extra dimension - such as the story of the New Zealand soldier’s bible, found on the battlefield in 1918, and, not least, Hodgson’s interesting post-war association with T. E. Lawrence. In short, it is an account to which I am sure I will return frequently in the future.’

Professor Peter Simkins MBE FRHistS, retired Senior Historian of the Imperial War Museum, Honorary Professor at the Centre for First World War Studies at the University of Birmingham.

‘This is the fascinating record of an individual who lived during one of the most traumatic periods of history. His descriptions of life as a soldier on the Western Front are clear and powerful, and the story of the Bible is truly moving. His memories as the printer of Seven Pillars of Wisdom involve exceptional recollections of one of the most enigmatic and iconic personalities of the twentieth Century.’

John T. Maguire M.A., military history researcher.

'This work of the life of Herbert Hodgson makes a significant contribution to the material about T. E. Lawrence and the physical production of the privately printed 1926 Subscribers Edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom for which Hodgson acted as pressman. Much exists about Lawrence's anxiety about publishing the work but very little on the difficulties surrounding the creation of the book on the press. The gap has now been filled by this book. Following the completion of his work on Seven Pillars Hodgson moved on to the Gregynog Press in Wales where he spent some nine years working as pressman on the production of twenty-four fine press books in the colophon of each of which his name appears. ... As a lifelong Lawrence collector and research scholar I welcome the appearance of this book with the fresh information it provides and the long overdue appropriate recognition of Herbert Hodgson.'

Paul F. Helfer, US Attorney at Law and T. E. Lawrence scholar.

'I cannot tell you how pleased I am that you have managed to get these memoirs into print at last, The book is really a compelling and enjoyable read ...'

Dorothy A. Harrop, author of A History of the Gregynog Press

The moving story of the lost Bible

Impressions of War relates an incident of a Bible found in the mud of the trenches in 1918. Here is more on this Bible story.

The Bible was kept by Bernard Hodgson, one of Herbert Hodgson's sons. Previous searches for the serial number in British Army archives had failed to find a match. Geoffrey M. Hodgson did an Internet search in 2010, to discover that the original owner of the Bible was a New Zealand soldier named Richard Cook, who lost the Bible in the trenches of Flanders in June 1917. He died in Passchendaele in October 1917.

How the Bible was found in 1918 and traced in 2010

Herbert Hodgson in 1917, when he was in the 1/24th (County of London) Battalion (The Queen’s), Royal West Surrey Regiment.

The Lost Bible, with the army serial number marked clearly on the top

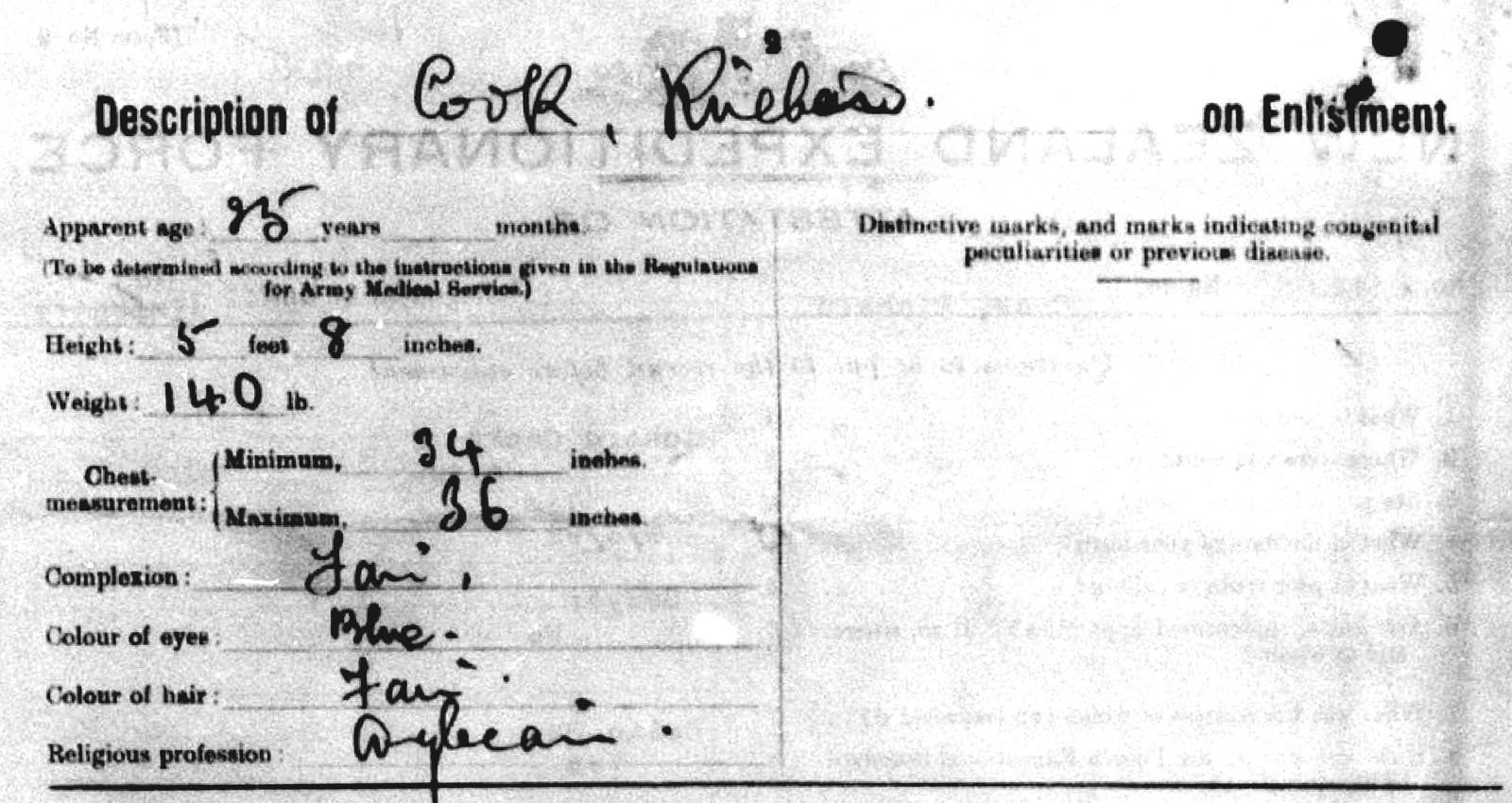

This Bible remained in the possession of Herbert Hodgson's family. Amazingly, 92 years later, its original owner was traced! A Web search on 8 June 2010 by Geoffrey M. Hodgson revealed that army service number 34816 was Private Richard Llewellyn Cook, of the 14th Company, 3rd Battalion of the Otago Regiment of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, son of Reuben and Mary Jane Cook, of Colac Bay, Southland, New Zealand.

Richard Llewellyn Cook (1891-1917)

Part of Richard Cook's Army Medical Record on Enlistment in New Zealand on 23 August 1916

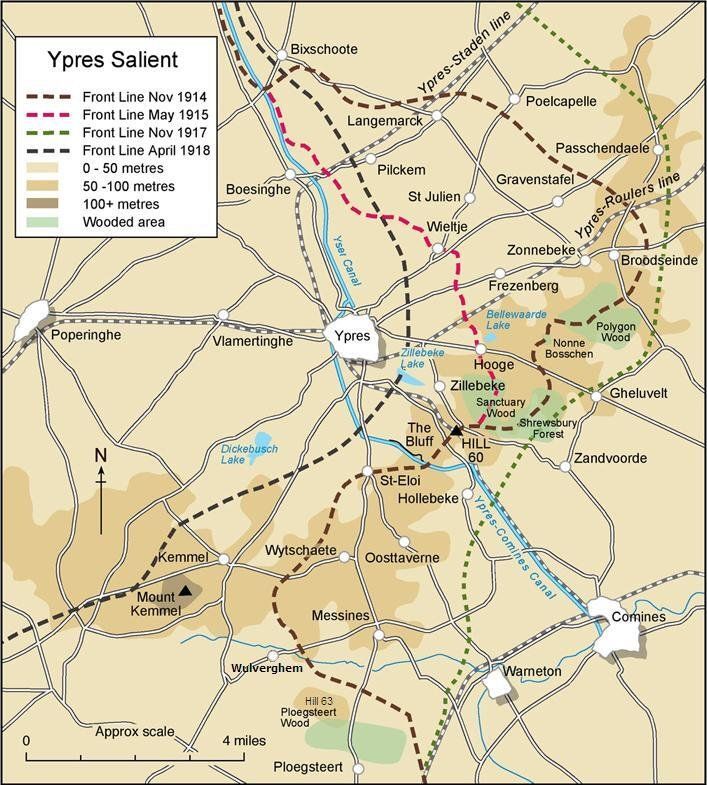

The New Zealand Expeditionary Force fought at Messines in June, at Polygon Wood near Ypres in September, and near Passchendaele in October 1917. All three locations are in Belgium. Hodgson’s battalion fought at the first of these only. Messines is where they both fought in 1917-18.

The Area Around Ypres (now Ieper) in Belgium

Richard Cook - From Messines to Passchendaele

According to The Official History of the Otago Regiment, of which Richard Cook was a member, his Company arrived at a place known as SP4 (Strong Point 4) on the Wulverghem-Messines road in March 1917.[1] Close to Wulverghem - which is 3 km west of Messines - SP4 was just beside North Midlands Farm. Together with North and South Midlands Farm it "was practically the mainstay of the front line system. It included a system of deep dug-outs and galleries connected with the trenches by stairways; the whole of the defences of this redoubt being such as to assure a protracted resistance." [2]

Messines and Wulverghem, Before 7 June 1917

See more detailed trench map of the same area below.

See more detailed trench map of the same area below.

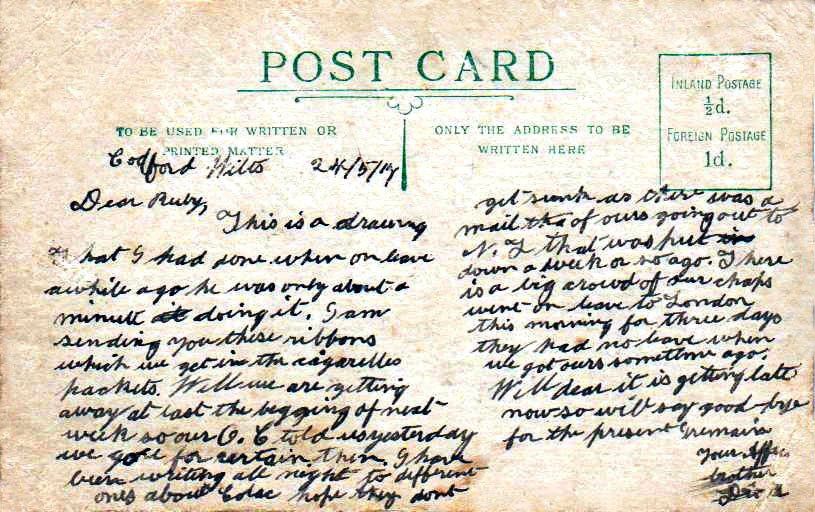

Postcard and Drawing of Richard Cook - Sent to his Adopted Sister Ruby on 24 May 1917

Richard Cook enlisted in New Zealand on 23 August 1916. His troopship left Wellington on 30 December and arrived in Devonport in England on 3 March 1917. He was sent to Codford on Salisbury Plain for training. From Codford Richard Cook sent a postcard and drawing of himself to his adopted sister Ruby (1904-1995) two weeks before the attack on Messines Ridge. Richard Cook writes on the postcard that they were informed by their commanding officer that "for certain" they were "getting away at last" in a few days, thus hinting at the big battle to come.

Comparison of the 4 in the date on the postcard with the 4 on top of the lost Bible reveals the same writing style with the distinctive loop in the bottom left corner of the integer, thus confirming the link made by the army serial number.

On 28 May he was sent through France to join his battalion on the front near Wulverghem in Belgium. A few days later, Cook was to loose his Bible in a Belgian trench. Five months later he was dead.

In the Battle of Messines Ridge of 7 June 1917 Richard Cook's 14th Company was ordered to attack roughly eastwards just north of the Wulverghem-Messines road. This mean that they would have gone over the top just north-west of Boyle's Farm. They reached the Messines-Wytschaete road near Swayne's Farm (see above map). [3]

The capture of the Messines Ridge was one of the most successful Allied operations of the War. It followed a huge explosion on 7 June 1917 – heard as far away as London and unrivalled until the atomic bombs of 1945 – caused by the detonation of mines in tunnels deep beneath the surface. The blast killed about 10,000 German soldiers and destroyed most of the fortifications on the ridge, as well as the town of Messines itself. This remains the deadliest man-made non-nuclear explosion in history. [4] The Otago Regiment played a major part in the capture of Messines and their heroic role is commemorated by a memorial in the town.

It seems that Richard Cook lost his Bible near Messines, possibly during heavy shelling near North Midland Farm, or while he was waiting at the front line to go over the top in the early hours of 7 June 1917.

Comparison of the 4 in the date on the postcard with the 4 on top of the lost Bible reveals the same writing style with the distinctive loop in the bottom left corner of the integer, thus confirming the link made by the army serial number.

On 28 May he was sent through France to join his battalion on the front near Wulverghem in Belgium. A few days later, Cook was to loose his Bible in a Belgian trench. Five months later he was dead.

In the Battle of Messines Ridge of 7 June 1917 Richard Cook's 14th Company was ordered to attack roughly eastwards just north of the Wulverghem-Messines road. This mean that they would have gone over the top just north-west of Boyle's Farm. They reached the Messines-Wytschaete road near Swayne's Farm (see above map). [3]

The capture of the Messines Ridge was one of the most successful Allied operations of the War. It followed a huge explosion on 7 June 1917 – heard as far away as London and unrivalled until the atomic bombs of 1945 – caused by the detonation of mines in tunnels deep beneath the surface. The blast killed about 10,000 German soldiers and destroyed most of the fortifications on the ridge, as well as the town of Messines itself. This remains the deadliest man-made non-nuclear explosion in history. [4] The Otago Regiment played a major part in the capture of Messines and their heroic role is commemorated by a memorial in the town.

It seems that Richard Cook lost his Bible near Messines, possibly during heavy shelling near North Midland Farm, or while he was waiting at the front line to go over the top in the early hours of 7 June 1917.

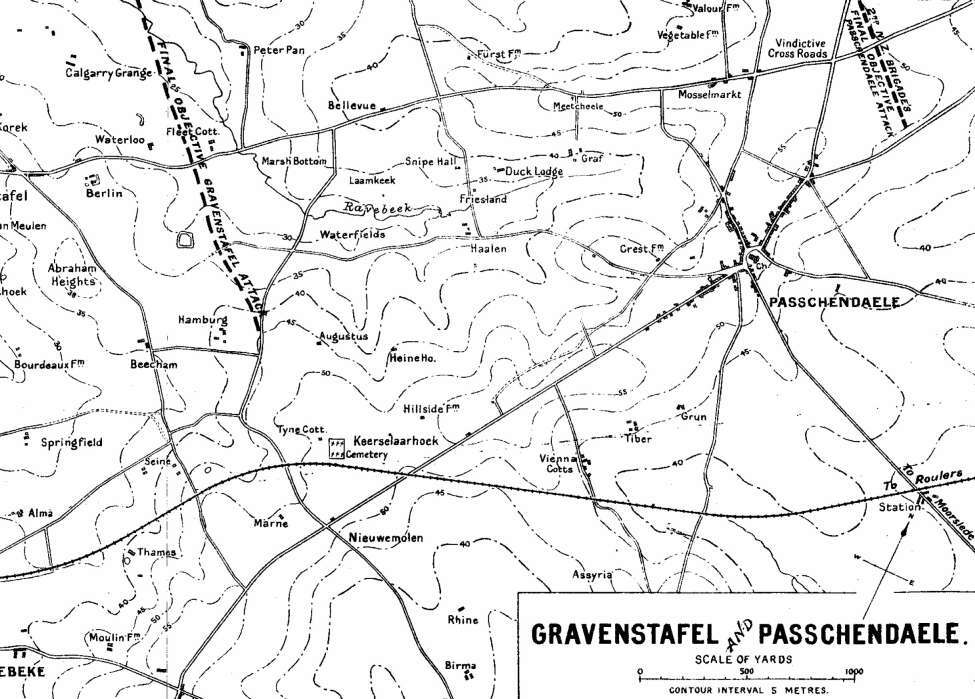

Several weeks later the Otago Regiment was in a major attack near Passchendaele. On the evening of 3 October 1917:

"troops of the 1st and 4th Infantry Brigades took up their positions for the attack against Gravenstafel and the Abraham Heights, which was launched on the following morning. It was in this attack ... that the 3rd Battalion of Otago Regiment was committed to its first big effort. The operation was extraordinarily successful. All objectives were captured and consolidated, 1,160 prisoners and 60 machine guns were accounted for by the two Brigades concerned, and the enemy suffered a very serious set-back." [5]

"troops of the 1st and 4th Infantry Brigades took up their positions for the attack against Gravenstafel and the Abraham Heights, which was launched on the following morning. It was in this attack ... that the 3rd Battalion of Otago Regiment was committed to its first big effort. The operation was extraordinarily successful. All objectives were captured and consolidated, 1,160 prisoners and 60 machine guns were accounted for by the two Brigades concerned, and the enemy suffered a very serious set-back." [5]

Gravenstafel Ridge and Passchendaele, October 1917

Because of the 3 March 1918 Brest-Litovsk treaty between the Germans and the new Communist Government in Russia, hostilities ended in the east, thus freeing up German troops for the Western Front. Their main offensives were around the Somme and Lys valleys, in March and April respectively. Hodgson fought in both these theatres of war. Tragically the German offensives of that year swept back over the ground at the Somme and Passchendaele that had been gained previously by the British at such human cost to both sides.

In their Lys Offensive the Germans recaptured Messines on 10 April 1918. On the following day several German units broke through the lines in the British sector of the Western Front and General Douglas Haig issued his famous order: "With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each us must fight on to the end."

Having fought in the Somme in March, Herbert Hodgson’s 9th Battalion of the Royal Irish Fusiliers moved on 11 April from the nearby town of Kemmel to "Stinking Farm", 2 km south-west of Messines. The entry for 12 April in the Battalion War Diary notes their subsequent retreat: "2am Moved to near Wulverghem. Headquarters at N Midland Farm. Enemy attacked, pressing back our line. Counter attack completely restored position. Casualties heavy." As the military historian Ian Passingham writes, the German "leading battalions were rapidly stopped near Wulverghem by stiff British resistance and then counter-attacks." [7]

An account of the role of some South African forces in the fighting in this area reads: “About four on the afternoon of the 11th [April] orders had been received from the 19th Division for a general withdrawal. The South Africans were to fall back to a line from North Midland Farm by Kruisstraat Cabaret and Spanbroekmolen to Maedelstaede Farm ... By 5 a.m. on the 12th [April] the South Africans were in their new front.” [8] The other places mentioned in this extract are north of North Midland Farm. This suggests that the South Africans held a line stretching almost due northwards from near the farm, perhaps corresponding to one or more of the trenches marked near "Spring Walk" in the top left corner of the map below. From this further evidence we can deduce the position of the line that all allied troops held in the early hours of 12 April.

Overall, the evidence suggests that on the morning of 12 April the 9th Battalion of the Royal Irish Fusiliers held the line close to North and South Midland Farms, and the South Africans were responsible for the sector further north. The front line on that day was probably a few hundred yards east and north-east of North Midland Farm. That is where Herbert Hodgson waited to go over the top early that morning in the counter-attack.

Tragically, Richard Cook received fatal injuries in this battle. Only 26 years of age, he wrote to his parents on 7 October from the No. 7 Canadian General Hospital (situated in the French coastal town of Étaples):

"Dear Father and Mother

A few lines to let you know that I am in this hospital wounded. We went over the top at six o'clock on Thursday morning Oct 4th and it was about an hour afterwards I got the two smacks, one in my left hip and the other in my right shoulder.

I am in this hospital until I am well enough to go to England. I hope you are both well at home. I am progressing favourably. Don't forget to drop me a line.

With my best love

Your loving son

Dick."

His condition was actually much worse than he suggested. The army chaplain wrote on 8 October:

"Dear Mrs Cook,

I am very sorry indeed to have to send such sad news about your son. Yesterday he was very ill and he dictated the enclosed letter to me. Towards evening he got worse and he passed away at 12.30 this morning. He was wounded by a gunshot in the thigh and shoulder.

We did all we could for him and his last hours were painless and peaceful. Poor chap, he did his duty towards God and towards man, and is now where pain and sorrow do not exist.

Please accept my warmest sympathy, and pray that Christ may give you his comfort and peace.

Yours faithfully

E. F. Pinnington

C of E Chaplain."

Richard Cook bled to death in a stretcher. With many others, he is buried in Étaples Military Cemetery in France. [6]

"Dear Father and Mother

A few lines to let you know that I am in this hospital wounded. We went over the top at six o'clock on Thursday morning Oct 4th and it was about an hour afterwards I got the two smacks, one in my left hip and the other in my right shoulder.

I am in this hospital until I am well enough to go to England. I hope you are both well at home. I am progressing favourably. Don't forget to drop me a line.

With my best love

Your loving son

Dick."

His condition was actually much worse than he suggested. The army chaplain wrote on 8 October:

"Dear Mrs Cook,

I am very sorry indeed to have to send such sad news about your son. Yesterday he was very ill and he dictated the enclosed letter to me. Towards evening he got worse and he passed away at 12.30 this morning. He was wounded by a gunshot in the thigh and shoulder.

We did all we could for him and his last hours were painless and peaceful. Poor chap, he did his duty towards God and towards man, and is now where pain and sorrow do not exist.

Please accept my warmest sympathy, and pray that Christ may give you his comfort and peace.

Yours faithfully

E. F. Pinnington

C of E Chaplain."

Richard Cook bled to death in a stretcher. With many others, he is buried in Étaples Military Cemetery in France. [6]

Where Herbert Hodgson found the Bible in 1918

Because of the 3 March 1918 Brest-Litovsk treaty between the Germans and the new Communist Government in Russia, hostilities ended in the east, thus freeing up German troops for the Western Front. Their main offensives were around the Somme and Lys valleys, in March and April respectively. Hodgson fought in both these theatres of war. Tragically the German offensives of that year swept back over the ground at the Somme and Passchendaele that had been gained previously by the British at such human cost to both sides.

In their Lys Offensive the Germans recaptured Messines on 10 April 1918. On the following day several German units broke through the lines in the British sector of the Western Front and General Douglas Haig issued his famous order: "With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each us must fight on to the end."

Having fought in the Somme in March, Herbert Hodgson’s 9th Battalion of the Royal Irish Fusiliers moved on 11 April from the nearby town of Kemmel to "Stinking Farm", 2 km south-west of Messines. The entry for 12 April in the Battalion War Diary notes their subsequent retreat: "2am Moved to near Wulverghem. Headquarters at N Midland Farm. Enemy attacked, pressing back our line. Counter attack completely restored position. Casualties heavy." As the military historian Ian Passingham writes, the German "leading battalions were rapidly stopped near Wulverghem by stiff British resistance and then counter-attacks." [7]

An account of the role of some South African forces in the fighting in this area reads: “About four on the afternoon of the 11th [April] orders had been received from the 19th Division for a general withdrawal. The South Africans were to fall back to a line from North Midland Farm by Kruisstraat Cabaret and Spanbroekmolen to Maedelstaede Farm ... By 5 a.m. on the 12th [April] the South Africans were in their new front.” [8] The other places mentioned in this extract are north of North Midland Farm. This suggests that the South Africans held a line stretching almost due northwards from near the farm, perhaps corresponding to one or more of the trenches marked near "Spring Walk" in the top left corner of the map below. From this further evidence we can deduce the position of the line that all allied troops held in the early hours of 12 April.

Overall, the evidence suggests that on the morning of 12 April the 9th Battalion of the Royal Irish Fusiliers held the line close to North and South Midland Farms, and the South Africans were responsible for the sector further north. The front line on that day was probably a few hundred yards east and north-east of North Midland Farm. That is where Herbert Hodgson waited to go over the top early that morning in the counter-attack.

Map of Trenches Near Messines in 1918

The image above is largely based on an original trench map dated 20 March 1918.

The image above is largely based on an original trench map dated 20 March 1918.

Note the results of the mine explosion of 7 June 1917 at Ontario Farm.

The June 1917 attack line of Richard Cook’s 14th Company in the Otago Regiment was just north of the Wulverghem-Messines road, as indicated by the green arrow on the map above.

The June 1917 attack line of Richard Cook’s 14th Company in the Otago Regiment was just north of the Wulverghem-Messines road, as indicated by the green arrow on the map above.

On 12 April 1918 the Germans advanced as far west and beyond the blue arrows, but were repulsed by Herbert Hodgson’s battalion just east of North Midland Farm. After he went over the top in the counter-attack, Hodgson moved further eastwards on the north side of the Wulverghem-Messines road. Either the Bible was lost by Richard Cook while he was close to that farm (probably during heavy shelling) , or Hodgson reached as far as the old 6 June 1917 front line, and this is where the Bible was lost by Cook and found by Hodgson.

Hodgson says that he fell and found the Bible after "the first few yards". This might suggest that the Bible was located very roughly about 400 yards north-east of North Midland Farm. On the other hand, the old 6 June 1917 front line was only about 200 yards further east. In any case, we can determine where the Bible was lost and found in a zone stretching only a few hundred yards.

Modern Map of the Wulvergem-Mesen (Wulverghem-Messines) Locality

The map is divided into kilometre squares.

Area marked in blue where the Bible was probably lost and found

Due to the effects of that shell-burst when he went over the top on 12 April 1918, Herbert Hodgson was given lighter duties for the remainder of the war. He returned to England in February 1919 and became the printer of the 1926 hand-printed craft edition of The Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T. E. Lawrence. He died in 1974 aged 81, leaving four sons and a daughter.

David Hodgson, one of Herbert Hodgson's sons, recollects: "I can remember my Dad holding the Bible in his hand with the words: 'I wonder what poor bugger lost this and it certainly did bring me luck.' Excuse the language, but this was my Dad's way of expressing his sympathy for a fallen comrade."

The Family of Richard Cook in New Zealand

Richard was much loved by his family and his death was a terrible blow. The Southland Times

in New Zealand reported the news:

"A gloom was cast over our little township on Thursday when word was received that Dick, as he was called, had died of wounds. He was the second son to leave for the front, and wanted to go there earlier in the war, but his parents kept him at home. Dick was always a willing hand whenever any sport was going on, and did his share of cricket, football, sawing and chopping. He was also a prominent member of the rowing club, as well as an old volunteer in the Colac Rifles. His brother, Bert, left with the Main Body from Canterbury and was wounded in the chest on Gallipoli but pulled through allright. George, another brother, did his share of fighting in South Africa. Now he is married and has a family around him."

In Colac Bay: A History (p. 139), Joan MacIntosh wrote:

"Only those who knew Granny [Mary Jane] Cook at the time will ever know the deep wrenching sorrow that clouded the loving mother's face when news came that 'my poor Dickie' had been killed ... an experience suffered by many families at Colac Bay these four years."

Some of Richard's siblings had died as children before him. Three had tragically drowned in a river accident in 1888. Richard was survived by his parents, Reuben (1840-1933) and Mary Jane (1848-1923) and brothers and sisters Louis George (1880-1951), Albert Henry (1886-1972), Isabella Jane (1888-1946) and (adopted sister) Ruby Bynon Cook.

"A gloom was cast over our little township on Thursday when word was received that Dick, as he was called, had died of wounds. He was the second son to leave for the front, and wanted to go there earlier in the war, but his parents kept him at home. Dick was always a willing hand whenever any sport was going on, and did his share of cricket, football, sawing and chopping. He was also a prominent member of the rowing club, as well as an old volunteer in the Colac Rifles. His brother, Bert, left with the Main Body from Canterbury and was wounded in the chest on Gallipoli but pulled through allright. George, another brother, did his share of fighting in South Africa. Now he is married and has a family around him."

In Colac Bay: A History (p. 139), Joan MacIntosh wrote:

"Only those who knew Granny [Mary Jane] Cook at the time will ever know the deep wrenching sorrow that clouded the loving mother's face when news came that 'my poor Dickie' had been killed ... an experience suffered by many families at Colac Bay these four years."

Some of Richard's siblings had died as children before him. Three had tragically drowned in a river accident in 1888. Richard was survived by his parents, Reuben (1840-1933) and Mary Jane (1848-1923) and brothers and sisters Louis George (1880-1951), Albert Henry (1886-1972), Isabella Jane (1888-1946) and (adopted sister) Ruby Bynon Cook.

War Memorial in Colac Bay, New Zealand, Commemorating 15 Men from the Town who Died in the First World War

Richard Cook's name is fourth on the list

Richard Cook's name is fourth on the list

Living descendants have been traced of Albert Henry, Isabella Jane and Ruby Bynon. Ruby's son, James Richard Matheson has the letter from Richard Cook dated 7 October 1917 and another letter informing Richard's parents of the death of their son the following day. James Matheson wrote on 16 June 2010:

"My mother was Ruby Bynon Cook and was adopted by Reuben and Mary Cook. My mother was extremely fond of her brother and told me many incidents in which he had been very kind to her. When Richard (Dick) went to war she felt a great loss and was devastated when word came through that he had died; she was only 12 or 13 when the news came through."

Richard J. Cook wrote on 17 June 2010:

"My mother in law phoned me this morning with an exciting story that appeared in the Otago Daily Times, Dunedin NZ, regarding my great uncle Richard L. Cook. Richie as he was known to his family, was the brother of my grandfather Albert H. Cook. I am named after Richard. My grandfather also server in the First World War; he was badly wounded at Gallipoli. Richard was the youngest son and his death was a great blow to my great grand mother, so I am told. She had also lost three children drowned in the [Mataura] River – a common fate in early NZ. My wife and I visited the grave of Richard in about 1998 at Etaples. It was very moving, especially as I share the same name as on the grave!.I understand from his war record that he died of bullet wounds to arm and hip; he appears to have bled to death on a hospital stretcher. Richard was loved by his family. My grandfather had a large portrait of the two of them over his mantelpiece. He was never forgotten, although the sadness and sense of loss passed, down the generations. Unfortunately my grand father's house burned down completely in 1972, and my grandfather died in the flames."

Endnotes

1. A. E. Byrne, Official History of the Otago Regiment, N.Z.E.F. in the Great War 1914-1918, Dunedin: Wilkie, 1921, pp. 159-61.

2. Op. cit., p. 161.

3. Op cit. pp. 173, 178.

4. Ian Passingham, Pillars of Fire: The Battle of Messines Ridge, June 1917, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1998.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_the_largest_artificial_non-nuclear_explosions accessed 19 Dec 2021.

5. A. E. Byrne, op. cit. p. 206.

6. Sources: extant letters; surviving relatives in New Zealand. During the First World War there were numerous British hospitals and reinforcement camps at Étaples.

7. Ian Passingham, The German Offensives of 1918, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2008, p. 93.

8. John Buchan, The History of the South African Forces in France, London: Thomas Nelson, 1920, p. 203:

2. Op. cit., p. 161.

3. Op cit. pp. 173, 178.

4. Ian Passingham, Pillars of Fire: The Battle of Messines Ridge, June 1917, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1998.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_the_largest_artificial_non-nuclear_explosions accessed 19 Dec 2021.

5. A. E. Byrne, op. cit. p. 206.

6. Sources: extant letters; surviving relatives in New Zealand. During the First World War there were numerous British hospitals and reinforcement camps at Étaples.

7. Ian Passingham, The German Offensives of 1918, Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2008, p. 93.

8. John Buchan, The History of the South African Forces in France, London: Thomas Nelson, 1920, p. 203: