Stevenson's Ghost

Travels without a Donkey in the Cévennes:

Being the account of a walk through the Velay and the Cévennes in France in July 2008

© Geoffrey M. Hodgson

From 3-9 July 2008 I walked 141 kilometres through Velay and the Cévennes in France, following much of Robert Louis Stevenson's route in 1878.

2 July 2008

The previous two nights I had stayed in a house rented by my brother and his family in the Department of Aveyron. I drove eastwards through Mende in the Cévennes and arrived at the village of La Bastide Puylaurent, at 1024 metres above sea level. It is a place of little note, yet rewarded with a sizable railway station, at the junction of lines west from Mende, south from Alès and Nîmes, and north to Clermont-Ferrand.

I checked into the Gîte d’Etape ‘L’Etoile’, formerly Hotel Ranc. It was built in the 1920s to serve as a ski resort in winter, and a retreat from summer heat of the Mediterranean coast. A declining business in an age of air-conditioning and easier mobility, it was bought by tall, amiable Belgian-Greek Philippe Papadimitrou Demaitre Pausenberger Vanniesbecq for 900,000 francs in the early 1990s.

It was at this Gîte that Nicholas Crane arrived one evening in the Autumn of 1992, on his seventeen-month 10,000 kilometre trek along Europe’s mountain spine from Cape Finisterre to Istanbul. This incredible journey is described in his magnificent book Clear Waters Rising (1996) that deserves its place in the classic writings on travel alongside Samuel Johnson and Robert Louis Stevenson. Crane had come through the northern sierras of Spain, the Pyrenees and the Cévennes to arrive at La Bastide. Afterwards he trekked northeast across the Ardèche plateau to cross the Rhône at La Voulte and head into the Alps.

And it was over a century earlier, on 26 September 1878, that Stevenson himself arrived at La Bastide with his small donkey Modestine on his journey south into the Cévennes. Four days earlier he had departed from Le Monastier-sur-Gazeille, where he had purchased this animal to carry his possessions. His journey ended at St Jean du Gard near Alès on 3 October, after a distance of 225 kilometres (140 miles). His second book, Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, was published a year later. It became a huge success, was translated into several languages, and launched his career as a writer at the age of 28.

The ghost of Stevenson helped to keep ‘L’Etoile’ shining. Strategically placed on both the route of the 1878 trek and a north-south railway line, ‘L’Etoile’ was quickly found on a Web search for available accommodation. The proprietor had cannily organised useful information on the walk, so that it would be picked up by keywords such as ‘Stevenson trail accommodation’ with the search engines. He also had websites in several languages.

Why had Stevenson set out this journey? Apart from the search for material for this second book, the explanations seem to be God and love. Since 1873 Stevenson had been living a Bohemian existence in and around Paris, where he fell in love with Fanny Osbourne, a married American woman ten years his senior. She was separated from her husband and living in France with their two children. In those more God-fearing days when divorce was difficult, Stevenson’s desires were frustrated by social convention and fear of parental disapproval. In 1878 Fanny returned to California to try to obtain a divorce, leaving Stevenson in France. Love-sick and alone, he headed south for his journey.

Why did he choose this route? Actually, it starts in the Velay region and the Cévennes are not reached until about half way. But the Velay region is less well known, and Travels with a Donkey in the Velay and the Cévennes is a less economical title. Stevenson travelled to Le Puy-en-Velay by train. It is an ancient city and one of the four starting points in France for the pilgrimage route to the shrine of St James in Santiago de Compostela. Within and around the town are some spectacular volcanic pinnacles or puys, oneabout 80 metres above street level. It seems that Stevenson came to the Velay because of its volcanoes. The region around the city of Le Puy is peppered with numerous volcanic cones, some active as recently as eight thousand years ago.

Geology in general and vulcanology in particular were enormously popular in Victorian times. Charles Darwin and others had challenged the belief in a Divine creation. Fossils and volcanoes were regarded as evidence of a much greater longevity of the Earth and the species upon it. Although his father was a strict Protestant, Stevenson regarded himself as an atheist. He came to Velay to witness evidence against the literal and fundamentalist interpretation of the Bible, according to which the Earth was created around six thousand years ago.

Stevenson was raised by his nanny, Alison Cunningham. She had strong Calvinist views. Under her strict regime Stevenson was obliged to pray regularly. Although he was very fond of this woman, he had to get her religious indoctrination out of his system.

Religion was also his stimulus for going to the Cévennes. Much of southern France became Protestant in the sixteenth century, and the whole area became enflamed in the long, barbarous Wars of Religion. After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, Protestants throughout France were ruthlessly persecuted and forced to worship in secret. Four hundred thousand left the country and many settled in England. In 1702 a Protestant revolt erupted in the Céveness. A guerrilla army kept the authorities in check for more than two years, and resistance smouldered for long after that. They were called Camisards after the Occitane word camisa for shirt, which differentiated them from the French royal army in its uniform and armour.

Why did I set out on this journey? Neither love, nor God. I did miss my wife, but she is not keen on longer walks and I would not ask that she join me. I wanted to get a bit fitter, lose a bit of weight and lower my cholesterol count. But all that I could do more effectively by a few regular hours in the pool of the gym. So what was the main reason? It was not God but email.

Email? Let me explain. I travel a great deal. Often a holiday is a few days added to a lecture trip in some attractive global location. The laptop is with me when I work and make presentations. Like everyone in a similar occupation, I am inundated by emails. Many are spam and can be deleted immediately. But there is a significant number among the remainder where the sender expects a response within two or three days. These modern locusts chew into available hours and require regular disinfection almost every day. The intended line between work and leisure begins to disappear.

It has all happened rather quickly. I remember surviving for a couple of months without email in 1996 when my email system at work needed fixing. I delighted in this severance, but I would not dare for it to be repeated today. In 1997 I took my computer with me on a family holiday when the children still accompanied us, to my wife’s disapproval. Pressure of work meant that I had to finish something important and behind schedule. By the early years of the new millennium the desire was for an Internet connection at the holiday hotel, to manage the flow of emails when away.

Other professionals were obviously in the same position, as within a few years any global hotel of standing was offering Internet access. At first the prices were exorbitant, but fierce competition to supply so many customers forced most hotels by 2008 to offer this service for free. In the Aveyron on the previous two mornings I had joined my brother – an account manager for a large drugs company – while both of us were supposed to be on holiday, to catch up with our urgent emails. This affliction is not confined to academics.

The only way is to go backpacking for several days. The laptop is too heavy to carry and must be left behind. The line between work and leisure becomes visible again. But it will not last for much longer. It is predicted that the ubiquitous hotel-room telly will be soon replaced by a multiple-purpose unit, linked to the Internet and serving not only as a computer and a television but also as an entertainment machine. Perhaps via biometric personal identification, such as the iris or the fingerprint, it will be possible to log on and access personal data and emails. Bars as well as hotels would provide this service. Perhaps we have ten years left before the laptop jettisoning manoeuvre is unviable. Even before the ubiquitous instalment of computer-television hybrids we have already small hand-held devices and telephones to access the Internet. Perhaps ten years is too optimistic.

So avoidance of email is the reason. But why did I choose the Stevenson Trail in particular? I am familiar with his works and I loved Treasure Island and Kidnapped as a child, but I now hold him in no special affection as a writer. If I had known of a trail associated with William Shakespeare, John Donne, Thomas Hardy or D. H. Lawrence, then it would have been further up my list of considerations.

Here age has a story to tell. I have done a lot of walking in mountains and I have especially enjoyed protracted backpacking in uplands alone and with friends. Five of us did a wonderful seven-day walk in the high Pyrenees in 1995. But as my fitness deteriorated, heavy backpacking expeditions on mountains in 2001 and 2006 were abandoned. It has become too much for me to climb for sustained periods with a heavy load including food for several days, cooking equipment and a tent. I have downgraded to expeditions requiring spare clothes and few additional items only.

Given this, there are several European long distance trails where overnight stops at catered accommodation are possible. My particular interest in the Stevenson Trail was prompted when our neighbour at our house in France gave me a French translation of Stevenson’s Cévennes Journal as a present. The trail was not far away from our house in France, and with relatively few arduous ascents it seemed a good route to try to regain some of my previous physical fitness.

Incidentally, the original notebook compiled by Stevenson while on his journey was re-discovered in the 1970s in Yale University Library in the USA, and then published in English and in French, to join the many editions of Travels with a Donkey proper.

If it were not for Treasure Island and Kidnapped, then few would have taken much notice and no-one would be walking Stevenson Trail today. Indeed, it was only after two world wars and the appearance of films and TV serials based in his works that the trail became established as a popular long-distance hike. An American named Betty Gladstone, accompanied by her twelve and eighteen year old daughters and a donkey, walked the whole route from Monastier to St Jean du Gard in May 1963. In 1965 she donated a commemorative granite plinth that records the start of Stevenson’s journey in Monastier. Two American women, Carolyn Patterson and Cotton Coulson, a senior editor and a photographer from National Geographic, set out from Monastier on 22 September 1977, exactly ninety-nine years after Stevenson. They too had a donkey named Modestine. They tried to follow the Scotsman’s route as closely as possible, but encountered the intrusions of motor traffic on some of the roads. They stayed the night in the same places as RLS, and slept rough where he had done so.

The illustrated story of the Patterson-Coulson journey appeared in the National Geographic in the following year, ready for the centenary. To mark that occasion, a group of six writers and journalists set out on the journey after a reception put on by the local politicians in Monastier. They were greeted en route by groups of locals and tourists.

Many others have now followed. The Stevenson Trail thus obtained iconic status less than thirty years ago. One can only imagine the many unacknowledged walking trails laid down by budding but unsuccessful writers, who failed to publish their Travels, or who never wrote a bestseller like Treasure Island, or who never had their works serialised on TV, or whose gem of a travel journal lies undiscovered in a library vault.

(Perhaps Shakespeare kept a journal when he wandered northwards to Scotland in his ‘lost years’ of 1585-1596, where he was thus inspired to write Macbeth. Such an unlikely supposition is no more fanciful than the boundless biographical speculations based on the minimal documented evidence that exists about his life.)

In the 1990s the Stevenson Trail became incorporated in the French system of walking routes – or grand randonnées – and it has been given the number GR70. Apart from the annoyances of motor traffic, following exactly in Stevenson’s footsteps is difficult for additional reasons. In places his precise route is unrecorded and unclear. He sometimes got lost. He had bad maps and he was not a good map-reader. Often the locals were unhelpful. Finally, the well-signed GR70 version of the walk has been designed to avoid some metalled roads where possible, rather than to follow Stevenson exactly.

The original Stevenson route has its meandering idiosyncrasies. Within its general drift from north to south, it lunges first to the west to Le Bouchet St Nicholas, moves south again, follows a large protrusion to the west through Fouzillac and Le Cheylard-l’Évêque, deviates eastwards to take in a Trappist Monastery, and takes a long veer westwards to reach Florac, before turning sharply southeast towards the final destination of St Jean du Gard.

Stevenson took twelve days, although he stopped for several half-days to write up his journal. I had only eight full days and two half days available, and no donkey to carry my luggage. So I decided to simplify the route a little, and cut a few corners where necessary.

3 July 2008

That morning, and without a tinge of remorse, I left my Ford Mondeo-stine in the car park at the gîte. I caught the 9.11am train from La Bastide Puylaurent to Langogne, a distance of 20 kilometres. With my carte senior the fare was less than 2 euros. From Langogne I took the bus to Le Puy-en-Velay at a cost six times more for less than twice the distance. The taxi for the mere 12 km to Monastier cost four times as much as the bus fare. I did a quick financial extrapolation and decided that I would have to start walking.

The bus trip from Langogne to Le Puy traversed the high Velay plateau on the N88 route nationale. I had passed this way several times before. Much of the area being over 1000 metres above sea level, it can be cool on an August day. From the car the scenery seems featureless and unattractive, punctuated by a few dreary villages. But away from the high road the area is serrated by attractive, steep-sided valleys, best accessed on foot. Also visible from Monastier and other parts of the Velay, are the many humps of extinct volcanoes. With more primitive and less rapid modes of conveyance, the area becomes more interesting.

Monastier has little to justify the month that Stevenson spent there in preparation for his walk. It is a jumble of old buildings with some minimal attempts at restoration. It does command a good vista of several of the surrounding volcanoes, and he sketched such a view in his Journal. As if to remind visitors that they had not stepped back into the nineteenth century, a five-metre banner commemorating the 130th anniversary of Stevenson’s walk was draped across the street. The same banner with its sponsorship logos from regional development authorities was found in prominent places in almost every town on the route. In typical French manner, at some stage the regional political élites had decided to use the RLS trek as a shameless means of promoting their area. Presumably they had marked the 120th and the 125th anniversaries, and they will go for the one in 2018 as well. 2028 will be a Jamboree.

It was just after midday and it had started to rain. I decided to stop at a local bar for a cup of tea. There were four locals at the bar and a middle-aged lady behind, who gave me a blank stare. One local slurred his speech and another seemed like a Gallic version of John Mills’ ‘Michael’ in the movie Ryan’s Daughter. One of the more sober locals kindly repeated my request for ‘un thé avec citron’ and the lady looked at me as if I was asking for an exotic drink. I had a coffee instead. The local politicians have more work to do, if promoting their region means making it accommodating for tourists.

I passed Mrs Gladstone’s granite plinth and headed towards the volcanic pimples. I could see several of them ahead through the drizzle, each reaching a height of about 1100 metres above the 1000 metre plateau. Once this district was a boiling cauldron of lava. I saw volcanic scree on the hillside and the path was covered with granite pebbles and rocks.

Given my afternoon start, my plan was to make the 13 kilometres to Goudet, where there is a gîte d’étape. Although the going was not flat I made good time. At 3pm I was at St Martin de Fugères, where I took a beer at a bar. I had two guidebooks with me, one in English and the other in French. The English guide noted that there was plenty of accommodation in Costaros, which was off the official GR70 route but a place through which Stevenson had passed. Temporarily more devoted to Stevenson’s actual route, I calculated I could make it to Costaros and find accommodation there. This would mean completing an overall distance of just over 23 kilometres in the day.

When I emerged from the bar the rain had stopped. I descended into the hamlet of Goudet, nestling in the infant valley of the Loire. Crossing the bridge, I had a good view of the Château Beaufort above the river. After taking a photograph I flicked through one of the guidebooks and discovered that Stevenson had sketched the same view in his Journal.

I made the same long ascent up the road from Goudet to Ussel, where RLS had had such difficulty encouraging Modestine. At the hamlet of Ussel the pack had fallen off her back, and Stevenson was obliged for a while to carry it himself, much to the laughter of the locals.

I pushed on and reached Costaros at about 6.30 pm. Stevenson described it as ‘an ugly village on the high road’. It has not changed, except that the high road is now the N88 and the town is made even more unpleasant by the noise of heavy lorries. I saw the sign of a hotel ahead but to my dismay I found it had closed down. I went into a bar for another beer and to enquire about accommodation. ‘Rien’ was the reply. The English guidebook, published in 1992, was hopelessly out of date. The locals had missed a trick and had not put a Stevenson banner across the street.

Being the account of a walk through the Velay and the Cévennes in France in July 2008

© Geoffrey M. Hodgson

From 3-9 July 2008 I walked 141 kilometres through Velay and the Cévennes in France, following much of Robert Louis Stevenson's route in 1878.

2 July 2008

The previous two nights I had stayed in a house rented by my brother and his family in the Department of Aveyron. I drove eastwards through Mende in the Cévennes and arrived at the village of La Bastide Puylaurent, at 1024 metres above sea level. It is a place of little note, yet rewarded with a sizable railway station, at the junction of lines west from Mende, south from Alès and Nîmes, and north to Clermont-Ferrand.

I checked into the Gîte d’Etape ‘L’Etoile’, formerly Hotel Ranc. It was built in the 1920s to serve as a ski resort in winter, and a retreat from summer heat of the Mediterranean coast. A declining business in an age of air-conditioning and easier mobility, it was bought by tall, amiable Belgian-Greek Philippe Papadimitrou Demaitre Pausenberger Vanniesbecq for 900,000 francs in the early 1990s.

It was at this Gîte that Nicholas Crane arrived one evening in the Autumn of 1992, on his seventeen-month 10,000 kilometre trek along Europe’s mountain spine from Cape Finisterre to Istanbul. This incredible journey is described in his magnificent book Clear Waters Rising (1996) that deserves its place in the classic writings on travel alongside Samuel Johnson and Robert Louis Stevenson. Crane had come through the northern sierras of Spain, the Pyrenees and the Cévennes to arrive at La Bastide. Afterwards he trekked northeast across the Ardèche plateau to cross the Rhône at La Voulte and head into the Alps.

And it was over a century earlier, on 26 September 1878, that Stevenson himself arrived at La Bastide with his small donkey Modestine on his journey south into the Cévennes. Four days earlier he had departed from Le Monastier-sur-Gazeille, where he had purchased this animal to carry his possessions. His journey ended at St Jean du Gard near Alès on 3 October, after a distance of 225 kilometres (140 miles). His second book, Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, was published a year later. It became a huge success, was translated into several languages, and launched his career as a writer at the age of 28.

The ghost of Stevenson helped to keep ‘L’Etoile’ shining. Strategically placed on both the route of the 1878 trek and a north-south railway line, ‘L’Etoile’ was quickly found on a Web search for available accommodation. The proprietor had cannily organised useful information on the walk, so that it would be picked up by keywords such as ‘Stevenson trail accommodation’ with the search engines. He also had websites in several languages.

Why had Stevenson set out this journey? Apart from the search for material for this second book, the explanations seem to be God and love. Since 1873 Stevenson had been living a Bohemian existence in and around Paris, where he fell in love with Fanny Osbourne, a married American woman ten years his senior. She was separated from her husband and living in France with their two children. In those more God-fearing days when divorce was difficult, Stevenson’s desires were frustrated by social convention and fear of parental disapproval. In 1878 Fanny returned to California to try to obtain a divorce, leaving Stevenson in France. Love-sick and alone, he headed south for his journey.

Why did he choose this route? Actually, it starts in the Velay region and the Cévennes are not reached until about half way. But the Velay region is less well known, and Travels with a Donkey in the Velay and the Cévennes is a less economical title. Stevenson travelled to Le Puy-en-Velay by train. It is an ancient city and one of the four starting points in France for the pilgrimage route to the shrine of St James in Santiago de Compostela. Within and around the town are some spectacular volcanic pinnacles or puys, oneabout 80 metres above street level. It seems that Stevenson came to the Velay because of its volcanoes. The region around the city of Le Puy is peppered with numerous volcanic cones, some active as recently as eight thousand years ago.

Geology in general and vulcanology in particular were enormously popular in Victorian times. Charles Darwin and others had challenged the belief in a Divine creation. Fossils and volcanoes were regarded as evidence of a much greater longevity of the Earth and the species upon it. Although his father was a strict Protestant, Stevenson regarded himself as an atheist. He came to Velay to witness evidence against the literal and fundamentalist interpretation of the Bible, according to which the Earth was created around six thousand years ago.

Stevenson was raised by his nanny, Alison Cunningham. She had strong Calvinist views. Under her strict regime Stevenson was obliged to pray regularly. Although he was very fond of this woman, he had to get her religious indoctrination out of his system.

Religion was also his stimulus for going to the Cévennes. Much of southern France became Protestant in the sixteenth century, and the whole area became enflamed in the long, barbarous Wars of Religion. After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, Protestants throughout France were ruthlessly persecuted and forced to worship in secret. Four hundred thousand left the country and many settled in England. In 1702 a Protestant revolt erupted in the Céveness. A guerrilla army kept the authorities in check for more than two years, and resistance smouldered for long after that. They were called Camisards after the Occitane word camisa for shirt, which differentiated them from the French royal army in its uniform and armour.

Why did I set out on this journey? Neither love, nor God. I did miss my wife, but she is not keen on longer walks and I would not ask that she join me. I wanted to get a bit fitter, lose a bit of weight and lower my cholesterol count. But all that I could do more effectively by a few regular hours in the pool of the gym. So what was the main reason? It was not God but email.

Email? Let me explain. I travel a great deal. Often a holiday is a few days added to a lecture trip in some attractive global location. The laptop is with me when I work and make presentations. Like everyone in a similar occupation, I am inundated by emails. Many are spam and can be deleted immediately. But there is a significant number among the remainder where the sender expects a response within two or three days. These modern locusts chew into available hours and require regular disinfection almost every day. The intended line between work and leisure begins to disappear.

It has all happened rather quickly. I remember surviving for a couple of months without email in 1996 when my email system at work needed fixing. I delighted in this severance, but I would not dare for it to be repeated today. In 1997 I took my computer with me on a family holiday when the children still accompanied us, to my wife’s disapproval. Pressure of work meant that I had to finish something important and behind schedule. By the early years of the new millennium the desire was for an Internet connection at the holiday hotel, to manage the flow of emails when away.

Other professionals were obviously in the same position, as within a few years any global hotel of standing was offering Internet access. At first the prices were exorbitant, but fierce competition to supply so many customers forced most hotels by 2008 to offer this service for free. In the Aveyron on the previous two mornings I had joined my brother – an account manager for a large drugs company – while both of us were supposed to be on holiday, to catch up with our urgent emails. This affliction is not confined to academics.

The only way is to go backpacking for several days. The laptop is too heavy to carry and must be left behind. The line between work and leisure becomes visible again. But it will not last for much longer. It is predicted that the ubiquitous hotel-room telly will be soon replaced by a multiple-purpose unit, linked to the Internet and serving not only as a computer and a television but also as an entertainment machine. Perhaps via biometric personal identification, such as the iris or the fingerprint, it will be possible to log on and access personal data and emails. Bars as well as hotels would provide this service. Perhaps we have ten years left before the laptop jettisoning manoeuvre is unviable. Even before the ubiquitous instalment of computer-television hybrids we have already small hand-held devices and telephones to access the Internet. Perhaps ten years is too optimistic.

So avoidance of email is the reason. But why did I choose the Stevenson Trail in particular? I am familiar with his works and I loved Treasure Island and Kidnapped as a child, but I now hold him in no special affection as a writer. If I had known of a trail associated with William Shakespeare, John Donne, Thomas Hardy or D. H. Lawrence, then it would have been further up my list of considerations.

Here age has a story to tell. I have done a lot of walking in mountains and I have especially enjoyed protracted backpacking in uplands alone and with friends. Five of us did a wonderful seven-day walk in the high Pyrenees in 1995. But as my fitness deteriorated, heavy backpacking expeditions on mountains in 2001 and 2006 were abandoned. It has become too much for me to climb for sustained periods with a heavy load including food for several days, cooking equipment and a tent. I have downgraded to expeditions requiring spare clothes and few additional items only.

Given this, there are several European long distance trails where overnight stops at catered accommodation are possible. My particular interest in the Stevenson Trail was prompted when our neighbour at our house in France gave me a French translation of Stevenson’s Cévennes Journal as a present. The trail was not far away from our house in France, and with relatively few arduous ascents it seemed a good route to try to regain some of my previous physical fitness.

Incidentally, the original notebook compiled by Stevenson while on his journey was re-discovered in the 1970s in Yale University Library in the USA, and then published in English and in French, to join the many editions of Travels with a Donkey proper.

If it were not for Treasure Island and Kidnapped, then few would have taken much notice and no-one would be walking Stevenson Trail today. Indeed, it was only after two world wars and the appearance of films and TV serials based in his works that the trail became established as a popular long-distance hike. An American named Betty Gladstone, accompanied by her twelve and eighteen year old daughters and a donkey, walked the whole route from Monastier to St Jean du Gard in May 1963. In 1965 she donated a commemorative granite plinth that records the start of Stevenson’s journey in Monastier. Two American women, Carolyn Patterson and Cotton Coulson, a senior editor and a photographer from National Geographic, set out from Monastier on 22 September 1977, exactly ninety-nine years after Stevenson. They too had a donkey named Modestine. They tried to follow the Scotsman’s route as closely as possible, but encountered the intrusions of motor traffic on some of the roads. They stayed the night in the same places as RLS, and slept rough where he had done so.

The illustrated story of the Patterson-Coulson journey appeared in the National Geographic in the following year, ready for the centenary. To mark that occasion, a group of six writers and journalists set out on the journey after a reception put on by the local politicians in Monastier. They were greeted en route by groups of locals and tourists.

Many others have now followed. The Stevenson Trail thus obtained iconic status less than thirty years ago. One can only imagine the many unacknowledged walking trails laid down by budding but unsuccessful writers, who failed to publish their Travels, or who never wrote a bestseller like Treasure Island, or who never had their works serialised on TV, or whose gem of a travel journal lies undiscovered in a library vault.

(Perhaps Shakespeare kept a journal when he wandered northwards to Scotland in his ‘lost years’ of 1585-1596, where he was thus inspired to write Macbeth. Such an unlikely supposition is no more fanciful than the boundless biographical speculations based on the minimal documented evidence that exists about his life.)

In the 1990s the Stevenson Trail became incorporated in the French system of walking routes – or grand randonnées – and it has been given the number GR70. Apart from the annoyances of motor traffic, following exactly in Stevenson’s footsteps is difficult for additional reasons. In places his precise route is unrecorded and unclear. He sometimes got lost. He had bad maps and he was not a good map-reader. Often the locals were unhelpful. Finally, the well-signed GR70 version of the walk has been designed to avoid some metalled roads where possible, rather than to follow Stevenson exactly.

The original Stevenson route has its meandering idiosyncrasies. Within its general drift from north to south, it lunges first to the west to Le Bouchet St Nicholas, moves south again, follows a large protrusion to the west through Fouzillac and Le Cheylard-l’Évêque, deviates eastwards to take in a Trappist Monastery, and takes a long veer westwards to reach Florac, before turning sharply southeast towards the final destination of St Jean du Gard.

Stevenson took twelve days, although he stopped for several half-days to write up his journal. I had only eight full days and two half days available, and no donkey to carry my luggage. So I decided to simplify the route a little, and cut a few corners where necessary.

3 July 2008

That morning, and without a tinge of remorse, I left my Ford Mondeo-stine in the car park at the gîte. I caught the 9.11am train from La Bastide Puylaurent to Langogne, a distance of 20 kilometres. With my carte senior the fare was less than 2 euros. From Langogne I took the bus to Le Puy-en-Velay at a cost six times more for less than twice the distance. The taxi for the mere 12 km to Monastier cost four times as much as the bus fare. I did a quick financial extrapolation and decided that I would have to start walking.

The bus trip from Langogne to Le Puy traversed the high Velay plateau on the N88 route nationale. I had passed this way several times before. Much of the area being over 1000 metres above sea level, it can be cool on an August day. From the car the scenery seems featureless and unattractive, punctuated by a few dreary villages. But away from the high road the area is serrated by attractive, steep-sided valleys, best accessed on foot. Also visible from Monastier and other parts of the Velay, are the many humps of extinct volcanoes. With more primitive and less rapid modes of conveyance, the area becomes more interesting.

Monastier has little to justify the month that Stevenson spent there in preparation for his walk. It is a jumble of old buildings with some minimal attempts at restoration. It does command a good vista of several of the surrounding volcanoes, and he sketched such a view in his Journal. As if to remind visitors that they had not stepped back into the nineteenth century, a five-metre banner commemorating the 130th anniversary of Stevenson’s walk was draped across the street. The same banner with its sponsorship logos from regional development authorities was found in prominent places in almost every town on the route. In typical French manner, at some stage the regional political élites had decided to use the RLS trek as a shameless means of promoting their area. Presumably they had marked the 120th and the 125th anniversaries, and they will go for the one in 2018 as well. 2028 will be a Jamboree.

It was just after midday and it had started to rain. I decided to stop at a local bar for a cup of tea. There were four locals at the bar and a middle-aged lady behind, who gave me a blank stare. One local slurred his speech and another seemed like a Gallic version of John Mills’ ‘Michael’ in the movie Ryan’s Daughter. One of the more sober locals kindly repeated my request for ‘un thé avec citron’ and the lady looked at me as if I was asking for an exotic drink. I had a coffee instead. The local politicians have more work to do, if promoting their region means making it accommodating for tourists.

I passed Mrs Gladstone’s granite plinth and headed towards the volcanic pimples. I could see several of them ahead through the drizzle, each reaching a height of about 1100 metres above the 1000 metre plateau. Once this district was a boiling cauldron of lava. I saw volcanic scree on the hillside and the path was covered with granite pebbles and rocks.

Given my afternoon start, my plan was to make the 13 kilometres to Goudet, where there is a gîte d’étape. Although the going was not flat I made good time. At 3pm I was at St Martin de Fugères, where I took a beer at a bar. I had two guidebooks with me, one in English and the other in French. The English guide noted that there was plenty of accommodation in Costaros, which was off the official GR70 route but a place through which Stevenson had passed. Temporarily more devoted to Stevenson’s actual route, I calculated I could make it to Costaros and find accommodation there. This would mean completing an overall distance of just over 23 kilometres in the day.

When I emerged from the bar the rain had stopped. I descended into the hamlet of Goudet, nestling in the infant valley of the Loire. Crossing the bridge, I had a good view of the Château Beaufort above the river. After taking a photograph I flicked through one of the guidebooks and discovered that Stevenson had sketched the same view in his Journal.

I made the same long ascent up the road from Goudet to Ussel, where RLS had had such difficulty encouraging Modestine. At the hamlet of Ussel the pack had fallen off her back, and Stevenson was obliged for a while to carry it himself, much to the laughter of the locals.

I pushed on and reached Costaros at about 6.30 pm. Stevenson described it as ‘an ugly village on the high road’. It has not changed, except that the high road is now the N88 and the town is made even more unpleasant by the noise of heavy lorries. I saw the sign of a hotel ahead but to my dismay I found it had closed down. I went into a bar for another beer and to enquire about accommodation. ‘Rien’ was the reply. The English guidebook, published in 1992, was hopelessly out of date. The locals had missed a trick and had not put a Stevenson banner across the street.

Château Beaufort at Goudet

I had the two options of either Le Bouchet five kilometres ahead or Goudet ten kilometres behind. I asked if I could use the bar phone, which turned out to be the proprietor’s mobile. Grudgingly he passed it to me and I booked a bed in the gîte in Le Bouchet. I said I would be there before 8pm.

A minute later the proprietor received a return call on the same phone, informing him that my communicant at Le Bouchet would come to collect me by car. How could I refuse this generosity, particularly when contrasted with the mean proprietor who charged me fifty cents for the phone call? I rationalised my contravention of the rule that I would travel on foot by noting that it was only five kilometres, and Le Bouchet was slightly further from tomorrow’s destination than Costaros. My kind host arrived and took me to Le Bouchet and his gîte communal, which means sleeping in a dormitory with others. I took one of the two spare beds available and dashed for the shower while it was free. My host and his wife also ran the local auberge, where I had a good meal with a notably excellent course of Puy lentils with cream.

I was asleep by 10pm, before my companions had come to the room. In the early hours I was awakened by what sounded like a generator outside. After a while I realised that it was the noise of a roommate’s groaning CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machine, designed to alleviate sleep apnoea by pumping air down the throat via a mask. I might have slept better with the sound of his snoring.

4 July 2008

I arose early to a grey, cold morning. Le Bouchet is yet another dismal village on the high plateau, with four months of winter and two of summer. Its cluster of dilapidated farms smelt of silage and cow shit. Yet its 130th anniversary banner was proudly displayed across the street. Why had Stevenson come to this dreary place, after a long trek westwards, taking him no further towards his final destination in the south? He was trying to find Lac du Bouchet, two kilometres to the north, which has a diameter of 800 metres and occupies a volcanic crater. Partly because of the unhelpful locals, he failed to find this feature. It was one of several of his worthless detours, yet it survives on the route at least because it is one of the few places in this district with accommodation.

I was early for the appointed hour of my breakfast. My baguette was delivered by van at 8am. It was not fresh and I guessed that it had been baked the preceding day. I sat down at a table in the bar with the accompanying coffee. Why do many French establishments still believe that it is sufficiently elegant to eat bread without a plate? A few minutes later two more Gallic Michaels tottered into the bar and ordered their alcoholic shots. Sure enough, if I lived in this place I would be driven to drinking at such an hour.

My kind host gave unprompted directions to the continuation of the Chemin de Stevenson from the village. It was a straight, solitary track across the meadows. There were many wild flowers and trees of scented elderflower. On the left there were several volcanic pimples, mostly about 1200 metres above sea level but no more than 100 metres above the plateau. Denuded monuments of earthly and ungodly powers.

In Britain a Munro is classified as a mountain of over 913 metres (3000 feet) above sea level. As a lapsed Munro-bagger it occurred to me that I could climb dozen of these pimples in a couple of days, thus bagging a good number of Gallic Munros. Then I remembered that to qualify a Munro has to be separated from other features by a drop of over 500 feet on every side. Despite each being almost as high as Ben Nevis, one at most of these volcanic pimples would qualify.

As I walked on the weather improved. After the village of Landos, the sun broke through the clouds and the air became pleasantly warm. I heard a fox cry out from a small wood upon one of the volcanic tops.

My English guidebook recommended the attractive and historic town of Pradelles as the destination for the day. The French guidebook, published in 2007, also claimed that there was accommodation there. It would have meant a day’s walk of 24 kilometres. But I kept open the option of pressing on another five kilometres to Langogne, where I had noticed several hotels on the preceding day.

The route began to descend slowly, with views westwards across the wide valley of the Allier. I passed through a pine forest and entered the town of Pradelles. Although also situated aside the dreaded N88, its interesting parts are sufficiently away from the traffic noise. I noted the remains of its town ramparts and gates, but like Stevenson I avoided the famous wooden Virgin of Pradelles in the Church of Notre Dame, brought back by a crusader and said to be responsible for a number of miracles.

The countryside changed as I left Volcanoland behind. Ahead was a rolling and much wooded landscape, reminiscent of parts of Northumberland. I pressed on to Langogne over open fields with a view of the large Reservoir de Naussac in the distance. I found a hotel in good time for a shower before dinner. Like me, Stevenson had made it to Langogne on the second day of his walk. His much earlier start from Monastier was compensated by my five-kilometre lift in a car. I was over a day ahead of my own schedule.

5 July 2008

For some obscure reason, Stevenson had headed southwest from Langogne towards the village of Cheylard l’Évêque. He planned to then go on to the village of Luc the next day. Why didn’t he take the direct southerly route to Luc through the attractive Allier valley, which would have meant one day’s travel rather than two? In fact he got lost before he reached Cheylard, and was obliged to sleep rough in a storm. Cheylard has no special point of interest, so why did he go there? Was it simply the name – meaning Cheylard-the-Bishop –and his enduring atheistical fascination with religion?

After the event he may have regretted this uncomfortable and seemingly worthless detour. Yet it prompted one of the most famous passages in his Travels in the Cévennes:

"Why anyone should desire to visit either Luc or Cheylard is more than my much-inventing spirit can suppose. For my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move; to feed the needs and hitches of our life more nearly; to come down off the feather-bed of civilisation, and find the globe granite underfoot and strewn with cutting flints. Alas, as we get up in life, and are more preoccupied with our affairs, even a holiday is a thing that must be worked for. To hold a pack upon a pack-saddle against a gale out of the freezing north is no high industry, but it is one that serves to occupy and compose the mind. And when the present is so exacting, who can annoy himself about the future?"

Clearly there is no special reason to take the detour to Cheylard l’Évêque. Today it is not even possible for anyone to claim to be following faithfully in Stevenson’s footsteps, for RLS himself became lost. I decided that I would take the direct route to Luc and on to La Bastide, where I had parked my car. I would follow the attractive route by ascending the narrowing Allier valley, cut through by the railway upon which I had travelled two days before. If the great affair is to move, I could thus take the route I wished, and Stevenson’s ghost would not be offended. The alternative route via Cheylard seemed mere pedantry.

There is something too be said for feeling more nearly ‘the needs and hitches of our life’. On my travels I have often come down off the feather-bed of civilisation. But being well over twice Stevenson’s age in 1878, descent onto the turf is more difficult, and I cherish a softened bed all the more.

So I started out on the 20 kilometres towards La Bastide. The picturesque upper valley of the Allier reminded me of the Tyne Valley above Hexham in Northumberland, which also carries a working railway. But I soon found a good reason to take the detour to Cheylard l’Évêque. There is no footpath along the valley and for most of the way I was obliged to trudge along the D906 road. The holiday traffic greatly detracted from the beauty of the place.

This area is known as Gévaudan. In 1764 a huge wolf was reported in the area. For three years the Beast of Gévaudan ravaged the land, reportedly killed over a hundred women and children. A wolf was found and killed, but the attacks continued. The King of France was so alarmed that he sent an expert hunter, who tracked down and shot a second beast. The attacks ceased. Now the Beasts of Gévaudan have four wheels.

The legend of the Beast of Gévaudan was an inspiration for a successful 2001 French film by Samuel Le Bihan entitled Brotherhood of the Wolf.

At one great bend in the river, followed dutifully by the main road and the railway, I took one short cut along a private road through a wood. Near a farm off the road at La Maguelone, I saw an ancient wayside cross girded by flowers. By midday I was at Luc, which Stevenson had taken two days to reach from Langogne. I chatted with the locals and one showed me a fine basket of mushrooms he had gathered in the fields. I rejoined the Stevenson trail and for some way it departed from the noisy D906. I got to La Bastide in the mid-afternoon. The temperature was displayed in the village as 30 degrees.

Obeying Roman Army rules, three days hard marching would be rewarded by a day’s rest and recuperation. I had booked in for two nights at the Gîte d’Etape ‘L’Etoile’. I had walked 63 kilometres in two-and-a-half days. I was well ahead of Stevenson and my own schedule. I opened up my car, took out my laptop, and began writing my notes of the journey. I managed to avoid my emails until the next day.

As I noted before, Stevenson had passed through La Bastide on his way from Luc. His immediate destination was the Trappist monastery at Notre-Dame-des-Neiges, requiring a detour three kilometres to the east. It was not simply to get a bed for the night. His preoccupation with godly matters remained. As he wrote in his Travels with a Donkey:

"I had rarely approached anything with more unaffected terror than the monastery of our Lady of the Snows – fear took hold of me from head to foot."

Clearly, religion in general – and fear of Catholicism in particular – was something he had to exorcise. Today the monks are no longer bound by strict vows of silence and they tempt tourists with sales of their home-made honey and table wine. I had no inclination to visit this Trappist tourist trap.

6 July 2008

Emulating Stevenson, I spent much of the day writing up my journal. I caught up with the global news. There were only two hundred emails to be processed. I had been let off lightly. It was a dull and cool day – more suited for rest than exploration.

7 July 2008

Apart from at the evening at the end, Abigail was the only Brit I talked to on my seven-day adventure. She was originally from South Wales but had been living and working in Dublin for several years. At breakfast that morning she said that she planned to get as far as the village of Le Bleymard. As this was my objective too, we agreed to walk together. As I paid the bill, Monsieur Philippe joked that we could cut our journey short by getting the morning train to Chasseradès. He said: ‘I shall not tell anybody’.

From La Bastide the GR70 makes yet another deviation from Stevenson’s historic route by climbing and skirting the hills to the right of the valley floor for six kilometres. There was not much traffic and we decided to stick to the road instead. Faithful to Stevenson rather than the GR bureaucrats, we would save up to an hour on a long day’s walk. Sure enough, we quickly regained the GR70 and were at Chasseradès in a couple of hours. It is a pretty village with a lovely twelfth-century Romanesque church, built on an outcrop of rock.

Although only about 1.5 metres tall, Abigail is a strong walker. Bits of conversation during the day led me to guess that she was a Roman Catholic. She told me that she had once walked the last hundred kilometres of the pilgrim’s route to Santiago de Compostela to obtain an indulgence to give to her brother for a wedding present.

The roadways of France have plentiful wayside crosses. I noticed that simpler crosses of plain iron were becoming more common than the RC-favoured ornament of the tortured Jesus. In this district there were no indulgences to be purchased for our pains.

The first ten kilometres of our walk were close to the railway from La Bastide to Mende. A single-line track being surveyed during Stevenson’s visit, it had suffered no Beeching and it was still running trains across the high terrain. From Chasseradès the path goes through the small villages of Mirandol and L’Estampe. Stevenson had noted that the ‘narrow street of Estampe was full of sheep, black and white all bleating and tinkling with bells around their necks.’ It was much quieter today.

The weather was cool but the cloud cover was diminishing. Our route turned south up into the hills and through forests of beech and pine. At the top of the ridge the rolling Cévennes came into view. The official GR70 takes a winding detour past the source of the River Lot. Imagining a place of little more interest than a gurgling ditch, we took a more direct route down a forest track through the hamlet of Les Alpiers to our destination in Le Bleymard. I saw an eagle rise far ahead, alarmed by our approach.

On the edge of the Cévennes National Park, the village of Le Bleymard bustled with just a little tourism. A coach party of Cambridgeshire sixth-formers were visiting the small supermarket. A gaggle of French cyclists in bright clothes paused beside the road. Like a flock of geese, they moved and swayed on their machines. After a while they suddenly glided off, to follow their tacit leader up the road.

It was here in Le Bleymard that I witnessed the dawn of Das Stevensonkitsch. Keyrings with stuffed, grey Modestines; t-shirts with a Stevenson-Modestine logo; posed postcard photos of men leading donkeys; and a comic book in French relating Stevenson’s Travels with a Donkey. A small start; a lot of potential for the future. How about pottery figures of Stevenson and Modestine for the mantelpiece? Or cuddlier Modestines to take to bed? Or plastic inflatable donkeys to ride in the swimming pool?

The Hotel le Remise at Le Bleymard offers half-board at excellent value. One of the waitresses at dinner was especially pretty, although she seemed new to the job and did not know the names of the cheeses on offer. Stevenson had noted the beauty of a waitress and chatted to her at Le Pont-de-Montvert, which was to be our destination the next day. Here was another entrepreneurial opportunity for the Tourist Board – ensure that every lodging in Le Bleymard, and especially in Le Pont-de-Montvert, has a pretty waitress, to ensure that every traveller in Stevenson’s footsteps can replicate the historic flirtation.

8 July 2008

Le Pont-de-Montvert was to be reached over Mont Lozère. Thirty kilometres from east to west, Nicholas Crane compared this mountain to a baguette. We were to cross from north to south. The first three kilometres were largely through forest, up to the ski station at 1421 metres above sea level. At a greater height than Ben Nevis, the resort was struggling in the age of cheap travel and global warming. The summit was just two kilometres ahead, the route across the moor being marked by ancient standing stones called montjoies.

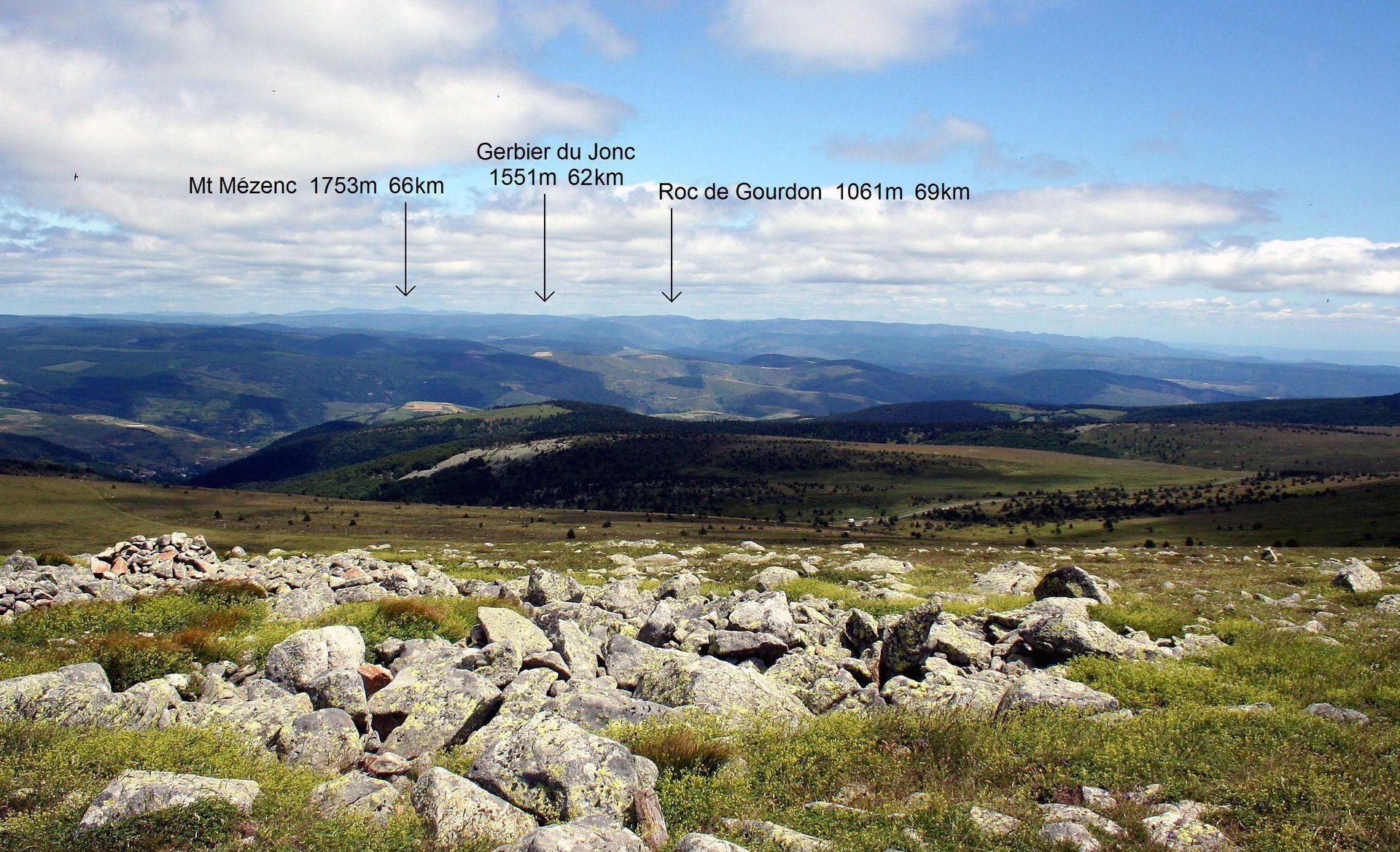

It was a bright, clear, sunny day and the view from the top was magnificent. To the west was the Ardèche plateau, with Mont Mézenc and Gerbier de Jonc. Beyond were the traces of the Rhône valley, leading south to the Camargue and the Mediterranean. Directly to our south were the rolling blue-green waves of the Cévennes. At 1699 metres this was the highest point of the whole journey, and exceeded in the whole of the Massif Central by Mont Mézenc and the volcanic puys of Mont Dore and Cantal.

A minute later the proprietor received a return call on the same phone, informing him that my communicant at Le Bouchet would come to collect me by car. How could I refuse this generosity, particularly when contrasted with the mean proprietor who charged me fifty cents for the phone call? I rationalised my contravention of the rule that I would travel on foot by noting that it was only five kilometres, and Le Bouchet was slightly further from tomorrow’s destination than Costaros. My kind host arrived and took me to Le Bouchet and his gîte communal, which means sleeping in a dormitory with others. I took one of the two spare beds available and dashed for the shower while it was free. My host and his wife also ran the local auberge, where I had a good meal with a notably excellent course of Puy lentils with cream.

I was asleep by 10pm, before my companions had come to the room. In the early hours I was awakened by what sounded like a generator outside. After a while I realised that it was the noise of a roommate’s groaning CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machine, designed to alleviate sleep apnoea by pumping air down the throat via a mask. I might have slept better with the sound of his snoring.

4 July 2008

I arose early to a grey, cold morning. Le Bouchet is yet another dismal village on the high plateau, with four months of winter and two of summer. Its cluster of dilapidated farms smelt of silage and cow shit. Yet its 130th anniversary banner was proudly displayed across the street. Why had Stevenson come to this dreary place, after a long trek westwards, taking him no further towards his final destination in the south? He was trying to find Lac du Bouchet, two kilometres to the north, which has a diameter of 800 metres and occupies a volcanic crater. Partly because of the unhelpful locals, he failed to find this feature. It was one of several of his worthless detours, yet it survives on the route at least because it is one of the few places in this district with accommodation.

I was early for the appointed hour of my breakfast. My baguette was delivered by van at 8am. It was not fresh and I guessed that it had been baked the preceding day. I sat down at a table in the bar with the accompanying coffee. Why do many French establishments still believe that it is sufficiently elegant to eat bread without a plate? A few minutes later two more Gallic Michaels tottered into the bar and ordered their alcoholic shots. Sure enough, if I lived in this place I would be driven to drinking at such an hour.

My kind host gave unprompted directions to the continuation of the Chemin de Stevenson from the village. It was a straight, solitary track across the meadows. There were many wild flowers and trees of scented elderflower. On the left there were several volcanic pimples, mostly about 1200 metres above sea level but no more than 100 metres above the plateau. Denuded monuments of earthly and ungodly powers.

In Britain a Munro is classified as a mountain of over 913 metres (3000 feet) above sea level. As a lapsed Munro-bagger it occurred to me that I could climb dozen of these pimples in a couple of days, thus bagging a good number of Gallic Munros. Then I remembered that to qualify a Munro has to be separated from other features by a drop of over 500 feet on every side. Despite each being almost as high as Ben Nevis, one at most of these volcanic pimples would qualify.

As I walked on the weather improved. After the village of Landos, the sun broke through the clouds and the air became pleasantly warm. I heard a fox cry out from a small wood upon one of the volcanic tops.

My English guidebook recommended the attractive and historic town of Pradelles as the destination for the day. The French guidebook, published in 2007, also claimed that there was accommodation there. It would have meant a day’s walk of 24 kilometres. But I kept open the option of pressing on another five kilometres to Langogne, where I had noticed several hotels on the preceding day.

The route began to descend slowly, with views westwards across the wide valley of the Allier. I passed through a pine forest and entered the town of Pradelles. Although also situated aside the dreaded N88, its interesting parts are sufficiently away from the traffic noise. I noted the remains of its town ramparts and gates, but like Stevenson I avoided the famous wooden Virgin of Pradelles in the Church of Notre Dame, brought back by a crusader and said to be responsible for a number of miracles.

The countryside changed as I left Volcanoland behind. Ahead was a rolling and much wooded landscape, reminiscent of parts of Northumberland. I pressed on to Langogne over open fields with a view of the large Reservoir de Naussac in the distance. I found a hotel in good time for a shower before dinner. Like me, Stevenson had made it to Langogne on the second day of his walk. His much earlier start from Monastier was compensated by my five-kilometre lift in a car. I was over a day ahead of my own schedule.

5 July 2008

For some obscure reason, Stevenson had headed southwest from Langogne towards the village of Cheylard l’Évêque. He planned to then go on to the village of Luc the next day. Why didn’t he take the direct southerly route to Luc through the attractive Allier valley, which would have meant one day’s travel rather than two? In fact he got lost before he reached Cheylard, and was obliged to sleep rough in a storm. Cheylard has no special point of interest, so why did he go there? Was it simply the name – meaning Cheylard-the-Bishop –and his enduring atheistical fascination with religion?

After the event he may have regretted this uncomfortable and seemingly worthless detour. Yet it prompted one of the most famous passages in his Travels in the Cévennes:

"Why anyone should desire to visit either Luc or Cheylard is more than my much-inventing spirit can suppose. For my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move; to feed the needs and hitches of our life more nearly; to come down off the feather-bed of civilisation, and find the globe granite underfoot and strewn with cutting flints. Alas, as we get up in life, and are more preoccupied with our affairs, even a holiday is a thing that must be worked for. To hold a pack upon a pack-saddle against a gale out of the freezing north is no high industry, but it is one that serves to occupy and compose the mind. And when the present is so exacting, who can annoy himself about the future?"

Clearly there is no special reason to take the detour to Cheylard l’Évêque. Today it is not even possible for anyone to claim to be following faithfully in Stevenson’s footsteps, for RLS himself became lost. I decided that I would take the direct route to Luc and on to La Bastide, where I had parked my car. I would follow the attractive route by ascending the narrowing Allier valley, cut through by the railway upon which I had travelled two days before. If the great affair is to move, I could thus take the route I wished, and Stevenson’s ghost would not be offended. The alternative route via Cheylard seemed mere pedantry.

There is something too be said for feeling more nearly ‘the needs and hitches of our life’. On my travels I have often come down off the feather-bed of civilisation. But being well over twice Stevenson’s age in 1878, descent onto the turf is more difficult, and I cherish a softened bed all the more.

So I started out on the 20 kilometres towards La Bastide. The picturesque upper valley of the Allier reminded me of the Tyne Valley above Hexham in Northumberland, which also carries a working railway. But I soon found a good reason to take the detour to Cheylard l’Évêque. There is no footpath along the valley and for most of the way I was obliged to trudge along the D906 road. The holiday traffic greatly detracted from the beauty of the place.

This area is known as Gévaudan. In 1764 a huge wolf was reported in the area. For three years the Beast of Gévaudan ravaged the land, reportedly killed over a hundred women and children. A wolf was found and killed, but the attacks continued. The King of France was so alarmed that he sent an expert hunter, who tracked down and shot a second beast. The attacks ceased. Now the Beasts of Gévaudan have four wheels.

The legend of the Beast of Gévaudan was an inspiration for a successful 2001 French film by Samuel Le Bihan entitled Brotherhood of the Wolf.

At one great bend in the river, followed dutifully by the main road and the railway, I took one short cut along a private road through a wood. Near a farm off the road at La Maguelone, I saw an ancient wayside cross girded by flowers. By midday I was at Luc, which Stevenson had taken two days to reach from Langogne. I chatted with the locals and one showed me a fine basket of mushrooms he had gathered in the fields. I rejoined the Stevenson trail and for some way it departed from the noisy D906. I got to La Bastide in the mid-afternoon. The temperature was displayed in the village as 30 degrees.

Obeying Roman Army rules, three days hard marching would be rewarded by a day’s rest and recuperation. I had booked in for two nights at the Gîte d’Etape ‘L’Etoile’. I had walked 63 kilometres in two-and-a-half days. I was well ahead of Stevenson and my own schedule. I opened up my car, took out my laptop, and began writing my notes of the journey. I managed to avoid my emails until the next day.

As I noted before, Stevenson had passed through La Bastide on his way from Luc. His immediate destination was the Trappist monastery at Notre-Dame-des-Neiges, requiring a detour three kilometres to the east. It was not simply to get a bed for the night. His preoccupation with godly matters remained. As he wrote in his Travels with a Donkey:

"I had rarely approached anything with more unaffected terror than the monastery of our Lady of the Snows – fear took hold of me from head to foot."

Clearly, religion in general – and fear of Catholicism in particular – was something he had to exorcise. Today the monks are no longer bound by strict vows of silence and they tempt tourists with sales of their home-made honey and table wine. I had no inclination to visit this Trappist tourist trap.

6 July 2008

Emulating Stevenson, I spent much of the day writing up my journal. I caught up with the global news. There were only two hundred emails to be processed. I had been let off lightly. It was a dull and cool day – more suited for rest than exploration.

7 July 2008

Apart from at the evening at the end, Abigail was the only Brit I talked to on my seven-day adventure. She was originally from South Wales but had been living and working in Dublin for several years. At breakfast that morning she said that she planned to get as far as the village of Le Bleymard. As this was my objective too, we agreed to walk together. As I paid the bill, Monsieur Philippe joked that we could cut our journey short by getting the morning train to Chasseradès. He said: ‘I shall not tell anybody’.

From La Bastide the GR70 makes yet another deviation from Stevenson’s historic route by climbing and skirting the hills to the right of the valley floor for six kilometres. There was not much traffic and we decided to stick to the road instead. Faithful to Stevenson rather than the GR bureaucrats, we would save up to an hour on a long day’s walk. Sure enough, we quickly regained the GR70 and were at Chasseradès in a couple of hours. It is a pretty village with a lovely twelfth-century Romanesque church, built on an outcrop of rock.

Although only about 1.5 metres tall, Abigail is a strong walker. Bits of conversation during the day led me to guess that she was a Roman Catholic. She told me that she had once walked the last hundred kilometres of the pilgrim’s route to Santiago de Compostela to obtain an indulgence to give to her brother for a wedding present.

The roadways of France have plentiful wayside crosses. I noticed that simpler crosses of plain iron were becoming more common than the RC-favoured ornament of the tortured Jesus. In this district there were no indulgences to be purchased for our pains.

The first ten kilometres of our walk were close to the railway from La Bastide to Mende. A single-line track being surveyed during Stevenson’s visit, it had suffered no Beeching and it was still running trains across the high terrain. From Chasseradès the path goes through the small villages of Mirandol and L’Estampe. Stevenson had noted that the ‘narrow street of Estampe was full of sheep, black and white all bleating and tinkling with bells around their necks.’ It was much quieter today.

The weather was cool but the cloud cover was diminishing. Our route turned south up into the hills and through forests of beech and pine. At the top of the ridge the rolling Cévennes came into view. The official GR70 takes a winding detour past the source of the River Lot. Imagining a place of little more interest than a gurgling ditch, we took a more direct route down a forest track through the hamlet of Les Alpiers to our destination in Le Bleymard. I saw an eagle rise far ahead, alarmed by our approach.

On the edge of the Cévennes National Park, the village of Le Bleymard bustled with just a little tourism. A coach party of Cambridgeshire sixth-formers were visiting the small supermarket. A gaggle of French cyclists in bright clothes paused beside the road. Like a flock of geese, they moved and swayed on their machines. After a while they suddenly glided off, to follow their tacit leader up the road.

It was here in Le Bleymard that I witnessed the dawn of Das Stevensonkitsch. Keyrings with stuffed, grey Modestines; t-shirts with a Stevenson-Modestine logo; posed postcard photos of men leading donkeys; and a comic book in French relating Stevenson’s Travels with a Donkey. A small start; a lot of potential for the future. How about pottery figures of Stevenson and Modestine for the mantelpiece? Or cuddlier Modestines to take to bed? Or plastic inflatable donkeys to ride in the swimming pool?

The Hotel le Remise at Le Bleymard offers half-board at excellent value. One of the waitresses at dinner was especially pretty, although she seemed new to the job and did not know the names of the cheeses on offer. Stevenson had noted the beauty of a waitress and chatted to her at Le Pont-de-Montvert, which was to be our destination the next day. Here was another entrepreneurial opportunity for the Tourist Board – ensure that every lodging in Le Bleymard, and especially in Le Pont-de-Montvert, has a pretty waitress, to ensure that every traveller in Stevenson’s footsteps can replicate the historic flirtation.

8 July 2008

Le Pont-de-Montvert was to be reached over Mont Lozère. Thirty kilometres from east to west, Nicholas Crane compared this mountain to a baguette. We were to cross from north to south. The first three kilometres were largely through forest, up to the ski station at 1421 metres above sea level. At a greater height than Ben Nevis, the resort was struggling in the age of cheap travel and global warming. The summit was just two kilometres ahead, the route across the moor being marked by ancient standing stones called montjoies.

It was a bright, clear, sunny day and the view from the top was magnificent. To the west was the Ardèche plateau, with Mont Mézenc and Gerbier de Jonc. Beyond were the traces of the Rhône valley, leading south to the Camargue and the Mediterranean. Directly to our south were the rolling blue-green waves of the Cévennes. At 1699 metres this was the highest point of the whole journey, and exceeded in the whole of the Massif Central by Mont Mézenc and the volcanic puys of Mont Dore and Cantal.

View from the Summit of Mont Lozère, 1699m

Coming off the summit we made our way through a huge flock of sheep, moving unguided as a herd. We descended through the pines, near where Stevenson had camped the night under the stars. Emerging from the forest, I missed the turn to Finiels. Instead we were marching south along a ridge towards a large rock formation. But the path petered out to nothing, so I suggested a short descent off the ridge to regain the path. This proved trickier than it seemed at first sight, because the rough, boulder-strewn hillside was boggy in parts with frequent brambles and nettles.

The GR path regained, we strolled into the pretty village of Le Pont-de-Montvert, built at the confluence of the Tarn, Rieumalet and Martinet rivers. It was here that the War of the Camisards had started.

François Langlade, the Abbé du Chayla, was the brutal Catholic governor of the district. He delighted in the torture of Protestant prisoners in the cellar of his house. In 1702 a gang of about fifty locals set out to free these captives. They murdered the Abbé at Le Pont-de-Montvert, thus triggering the uprising of the Camisards. Esprit Séguier, the leader of the killing, was caught within a few days. His right hand was severed before he was burnt alive. Les autres, duly encouraged, burned Catholic churches and murdered the priests. The Protestants organised themselves into a guerrilla army, under the leadership of Jean and Roland Cavalier. The guerrillas took advantage of the remote mountain topography. The royal army burned hundreds of local villages and massacred their inhabitants. The Camisards suffered a major defeat in 1704 and their leaders were betrayed, but scattered fighting went on until 1710. A small Protestant community survived and was largely left in peace, especially after the death of Louis XIV in 1715. Revolt and resentment came finally to an end only when the revolutionary government of 1789 granted religious freedom to the Protestants.

When Stevenson arrived in 1878 he delighted that the majority in the locality remained Protestant. His intellectual and emotional entanglement with religion survived his atheism. He described the War of the Camisards as "a romantic chapter" in "the history of the world." It is a shame that he did not dramatise these historic events in a full-scale novel. On the other hand, if he had, the area would have long overwhelmed and spoiled by tourists. Stevenson saved the splendid isolation of the Cévennes.

The GR path regained, we strolled into the pretty village of Le Pont-de-Montvert, built at the confluence of the Tarn, Rieumalet and Martinet rivers. It was here that the War of the Camisards had started.

François Langlade, the Abbé du Chayla, was the brutal Catholic governor of the district. He delighted in the torture of Protestant prisoners in the cellar of his house. In 1702 a gang of about fifty locals set out to free these captives. They murdered the Abbé at Le Pont-de-Montvert, thus triggering the uprising of the Camisards. Esprit Séguier, the leader of the killing, was caught within a few days. His right hand was severed before he was burnt alive. Les autres, duly encouraged, burned Catholic churches and murdered the priests. The Protestants organised themselves into a guerrilla army, under the leadership of Jean and Roland Cavalier. The guerrillas took advantage of the remote mountain topography. The royal army burned hundreds of local villages and massacred their inhabitants. The Camisards suffered a major defeat in 1704 and their leaders were betrayed, but scattered fighting went on until 1710. A small Protestant community survived and was largely left in peace, especially after the death of Louis XIV in 1715. Revolt and resentment came finally to an end only when the revolutionary government of 1789 granted religious freedom to the Protestants.

When Stevenson arrived in 1878 he delighted that the majority in the locality remained Protestant. His intellectual and emotional entanglement with religion survived his atheism. He described the War of the Camisards as "a romantic chapter" in "the history of the world." It is a shame that he did not dramatise these historic events in a full-scale novel. On the other hand, if he had, the area would have long overwhelmed and spoiled by tourists. Stevenson saved the splendid isolation of the Cévennes.

Le Pont-de-Montvert

We were drinking our cool beers in a bar only twenty metres from the spot in front of the clock tower where Esprit Séguier was burnt alive. Like me, Abigail did not have enough available time to complete the whole route, but in true pilgrimage fashion she wanted to reach the end of Stevenson’s walk at St Jean du Gard. She would get a taxi that evening to Florac and move on from there the next day. Perhaps she sensed my preference for being alone, or had had enough of my navigational errors.

I booked in to an indifferent and over-priced small hotel in the village. Yet there I had my best sleep for weeks.

9 July 2008

After flirting with the waitress at Le-Pont-de-Montvert, Stevenson had taken the road down the Tarn valley westwards towards Florac, sleeping out on the way. This route is now the busy D998. ‘For technical reasons’ (it was described in bureaucratic French somewhere), the GR70 ascends south onto the high ridge, turns west over the Signal de Bouges (1421m), follows the ridge for much of its extent and reaches Florac in an overall trek of 28 kilometres.

I booked in to an indifferent and over-priced small hotel in the village. Yet there I had my best sleep for weeks.

9 July 2008

After flirting with the waitress at Le-Pont-de-Montvert, Stevenson had taken the road down the Tarn valley westwards towards Florac, sleeping out on the way. This route is now the busy D998. ‘For technical reasons’ (it was described in bureaucratic French somewhere), the GR70 ascends south onto the high ridge, turns west over the Signal de Bouges (1421m), follows the ridge for much of its extent and reaches Florac in an overall trek of 28 kilometres.

Near the Summit of Le Signal de Bouges (1421m)

It was a crystal blue day, and the GR70 clearly took precedence over any fidelity to Stevenson. In my ascent from the village I met a friendly donkey, as if to remind me of Modestine. The cool shade of the pines was welcome as the sun became fiercer. These were the woods from which the Camisard army had launched its operations.

Near the top of the ridge the GR70 emerges into open country and the summit of the Signal du Bouges is reached at 1421 metres. At times the views were magnificent. Added to this were carpets of flowering heather capping much of the ridge. I overtook two French couples taking the same route and met a very short man with a dog coming the other way. It was the hottest day I had experienced on my whole journey, and before the end I ran out of water. It was a long and tiring stretch, but the most spectacular of my whole journey. Abigail had missed this treat.

With a fatigued pace I made my way into Florac and booked into a hotel. The next day on the official route seemed less attractive, and I decided to end it there. I had walked 141 kilometres in six days. Stevenson had taken nine to reach Florac, although he had taken several half-day breaks to write up his journal. My GPS reported just over 30 hours overall of walking time and 17 hours of stops. My total ascent had been 2328 metres.

Near the top of the ridge the GR70 emerges into open country and the summit of the Signal du Bouges is reached at 1421 metres. At times the views were magnificent. Added to this were carpets of flowering heather capping much of the ridge. I overtook two French couples taking the same route and met a very short man with a dog coming the other way. It was the hottest day I had experienced on my whole journey, and before the end I ran out of water. It was a long and tiring stretch, but the most spectacular of my whole journey. Abigail had missed this treat.

With a fatigued pace I made my way into Florac and booked into a hotel. The next day on the official route seemed less attractive, and I decided to end it there. I had walked 141 kilometres in six days. Stevenson had taken nine to reach Florac, although he had taken several half-day breaks to write up his journal. My GPS reported just over 30 hours overall of walking time and 17 hours of stops. My total ascent had been 2328 metres.

Ridge Path towards Florac